Today we will be discussing the ag industry with ag author, speaker, comedian, and personality – Damian Mason. Damian speaks on topics surrounding business and agriculture to keep audiences up to date with a touch of humor.

RENEE HANSEN: Damian, welcome to the Premier Podcast. So glad to have you here. You have a wonderful background as a businessman, an agriculturist, a speaker, a podcaster, an author and a consultant, but also, I think, importantly for our listeners is that you’re also a farmer. So, can you just tell our listeners a little bit about your farm?

DAMIAN MASON: Yeah, so I was raised on your basic Midwestern dairy farm. We milked about 60 cows and farmed 500 acres, most of it rented. My grandfather came to this country as a herdsman, and my father was raised milking cows for other people on their farms. My father lost his arm as a little boy and got an insurance settlement. And when he was 21 years old, he put that down on a chunk of ground — not a very good piece of farm ground, the kind that nobody else wanted, which is why the Masons ended up with it. So, that’s a neat story. I own the homeplace now. I don’t live there. I live a couple miles north of where I was raised, on a 200-acre chunk of ground that my wife and I bought in 2006 and renovated. So, I’ve been a farm guy. I love the farm thing. I rent my ground out to a large-scale dairy operator now. I manage the timber here, and then I travel around the country working with corporations and associations. In fact, your husband has been one of my clients, and I enjoy that aspect of my work. I have a degree in agricultural economics from Purdue. I went into corporate sales in 1994. That all changed. I quit my corporate job to pursue a career in political comedy. I turned that into a business and then built on that and sort of created the next thing and the next thing. And here we are now. It’s been 26 years, almost 27 now, that I haven’t had a real job. I tend to still carve out a niche in the business of agriculture.

RENEE HANSEN: Pretty well rounded.

DAMIAN MASON: Yeah, and as you said, I spent six months taking improvisational acting and scene-writing classes at Second City Chicago. There was a time when I thought I might end up on Saturday Night Live, but maybe I’m too conservative. But it didn’t happen, and that’s the way this thing goes. But it’s been an interesting ride. As a comedian with an ag background, I tell my ag people I work with now the benefit is comedy teaches you to be an observer. Because comedy’s very first thing is observation. You begin with observing, and then you put your point of view and perspective on that observation, and you deliver it with a punchline. Easy to explain, hard to actually execute, and certainly even harder to turn into a business. But comedy is just observation, point of view and perspective to deliver the punchline. Now, I do that about the business of agriculture as an ag commentator. I say, here’s the observation: “Oh yeah, I guess I heard something about that.” Now, here’s a perspective you haven’t considered. Here’s a juxtaposition: “Oh.” And then instead of a punchline, here’s the results. So, that’s kind of what we do now. That’s a big part of what I do. It’s sort of bringing the ag thing back to you with a different perspective.

RENEE HANSEN: Yeah, and that’s really why we wanted to have you on the podcast today. I think you offer a different perspective, and you also talked about execution. And I think that’s partially where Premier Crop is. We’re really trying to help growers with how they execute the way they do their business. And we’re trying to change the narrative a little bit of how they can be more efficient in farming. And I think you’ve got a really great perspective of being in the business of agriculture, talking about agriculture, farming. Can you tell and share with our listeners some of the trends that you’ve seen over the years?

DAMIAN MASON: Trends that I see: obviously, the trend to consolidation. That’s been going on forever and ever. 200 years ago, somebody sold their 10 acres and went and got a job at the textile mill along the river and handed their hoe to the neighbor and said: “Here. You go out there and hoe those plants.” So, that’s been happening forever. What I see as a trend that a lot of our ag people are kind of seeing but not fully embracing or accepting it as a reality or, worse yet, understanding what it means to them is a consumer-driven marketplace. All businesses are consumer driven. This idea of: “Oh, you work for yourself. You’re a farmer.” Well, that’s complete nonsense. If you work for yourself, you run out of your own money. You work for consumers. We all do. Premier Crop Systems works for its customers.

You, Renee, do not work for Dan. You work for those customers that pay for your product. We all work for customers. Ag works for consumers. 100 years ago, we did not have surpluses. That’s when we started having surpluses. For 9,900 years of agricultural evolution, we had food, but we still didn’t have very good food or very much food. Now, we have surplus food, and we have Whole Foods. We have Amazon. We have Uber Eats. We have good food in copious quantities. We still, in agriculture, think it’s 1900. We say: “We went out there and produced a whole bunch of corn. What the hell more do you want? Now, eat it.” And the consumer’s saying: “I can make a lot of different selections here. I can just get on my app and order up anything.” So, we probably need to catch up with them because forever we thought: “Hey, we produced this amazing amount of product. Now, just be happy.” Well, they’re not unhappy. They’re just more selective. Because if you give a child that’s never had a toy a block of wood, he’s got a toy. Now, if you give a child in America a block of wood who has every toy conceivable, they’re going to say: “What am I supposed to do with this?” That’s our consumer when it comes to food.

DAN FRIEBERG: Hey, Damian, I know this may be too raw to talk about right now, but what are we going to change? What’s going to change because of COVID in food and ag? And maybe we’re too much in the throws, and it’s too early or whatever. It seems like that’s one where there are probably insights that you might have that others haven’t even thought about.

DAMIAN MASON: COVID did a few things for every consumer in America, and I’m talking about North America. I’m not a consumer in Australia, although a lot of the exact trends extrapolate. First off, the American consumer has not ever — at least the ones that we’re talking about that are 50, 60, 70, 80 years old — has never gone to the store and seen barren shelves. That put the fear of God into people. So, that made there be a certain appreciation for food supply, but it also illustrated the food ignorance. Then, you had people taking to social media, saying: “Those farmers in Wisconsin who are dumping milk should be criminally prosecuted because there are people who can’t get milk.” And, of course, I go on social media and say: “Because you can’t take 8,500-gallon tanker trucks of raw milk to a food bank.” They don’t understand the supply chain, which brings us, then, to what else it revealed. It revealed to us that our supply chain was amazing. It was tight. It was efficient, but just-in-time manufacturing, the Japanese concept that created their efficiency — if you look up “just-in-time” and do the research, and I took some economics classes and loved to study it — it really came to the United States in the 1990s. It’s like, why did Japan kick our butt on auto manufacturing? Because they had so little supply and so depleted capital after World War II that the Japanese country said: “For us to get our economy going again, we’re going to have to be very lean, very efficient and maximize what we have.” So, they invented this concept of just-in-time manufacturing: getting a fender for a car one-and-a-half hours to the factory before it gets put on the car, meaning we didn’t have a warehouse sitting over here with fenders in it for 90 days, holding up our capital. We extrapolated those concepts to our food supply and said: “Let’s get those hogs to this facility, and they’re going to walk off that trailer. And within an hour that they walk off that trailer, they’re going to come out as pork chops down at the end of this plant.”

I might be off by a couple of hours, but the point is we got real, real lean. Well, that’s good and efficient for meat processors. But also, then, when we started having meat plant closures because the workers were infected with coronavirus — that plant got shut down in Sioux Falls that is five percent of our nation’s pork processing quantity — then, all of a sudden, there are people that are saying: “I’ve got to run and grab pork.” And then, we said: “Man, we’ve got some meat shortages.” And then Costco puts out signs that say: “No more than two packages of meat.” And everybody says: “What the heck is going on?” We’ve got about 14 days of cold storage in the United States of America per my research. There was an article in the Wall Street Journal a couple of weeks ago that said, right now, cold storage is a hot investment. Companies are going to buy and build more cold storage. And you say: “Well, that hurts efficiency. It’s going to drive up prices.” I think what we learned was food is so cheap in the U.S., with only 6.4 percent of our income being spent on food. We can probably throw a few more nickels per pound at pork chops to make sure we have them. So, I believe that we’ll probably build up a bigger supply, and we’ll put a little more slack in the system — a little less J.I.T. and a little bit more slack. That’s my observation. However, we always, then, in food production, get back to: “How cheap can we make it?” And I think we should probably get more of: “How much can we build some slack in the system or put more supply in there, should we have more of these disruptions?”

DAN FRIEBERG: And to your point, Damian, there’s a lot of the commodity grains that have been what the U.S. has exported around the world. It seems like world trade is going to be redone, and I don’t know what we become. There’s a lot of talk about manufacturing being brought back to the country and that, post-COVID, every country might become less dependent on other countries.

DAMIAN MASON: Yeah, well, what happens? You go through a big scare, and then you say: “What did we learn there?” It’s a little bit like: “huff and puff and blow your house down.” I’m never going to be dependent on somebody else. I’m going to be more prepared. It takes a big scare to, then, say: “What are we? The three little pigs?” Remember, everything in life goes back to the three little pigs: the straw house, the twig house, the brick house. So, the better you can build your brick house, the more you can, then, be insulated from foreign shocks, from derechos, from trade wars, from threats of war, whatever that should be. The thing is, over time, you tend to let your guard down. We probably, as the United States of America — this is one thing that I’ve been saying to my audiences for a long time — we are an export-driven ag because we’ve got 330 million people. There are 7.7 billion people on Earth. For years and years and years — centuries, in fact — we saw that we could make more food than we could ever use here, for the last several years anyway, and there are other countries that can’t. That’s changed, guys. Renee, Dan, let’s face it: Ukraine learned how to grow corn, and Brazil learned how to grow soybeans. So, the idea that we’re always just going to be able to put stuff on a barge and find somebody that’ll give us money for it is, frankly, a little short-sighted. And so, that’s where I say: “Let’s embrace the idea that our consumers will pay more and will want a more diverse product and possibly will, after things like this and threats of war and trade strife, buy an American product and pay more for it.” So, I think there is something to that. Now, will they pay more for an American soybean versus a Brazilian soybean? They don’t know the difference. So, it’s going to have to be the next thing beyond that, the value-added product that we can pitch and push and promote as an American value-add.

RENEE HANSEN: So, if there’s going to be so much surplus, farmers now are trying to be more efficient. They’re trying to grow more. They’re trying to get higher yields. What do you see happening? Do you think that farmers are going to start creating more diversity with the farms that they currently have? Because it’s hard to grow. And in this age right now, too, farmland is very expensive — unless you’re a large operation or you have the funds. You are able to purchase more land. What is your perspective on growing more with what you have or becoming more diversified?

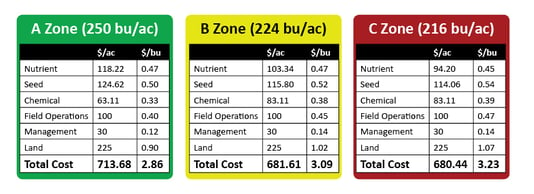

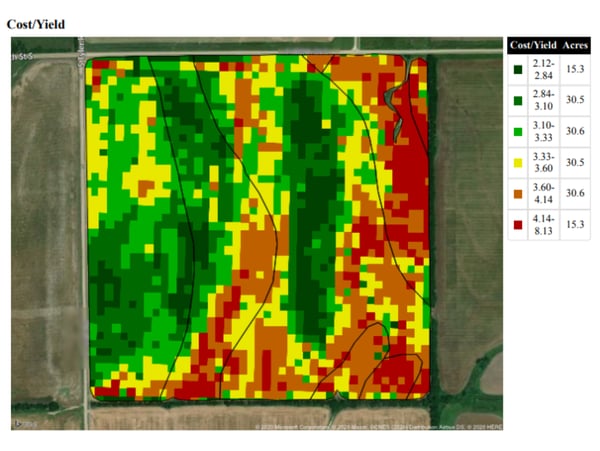

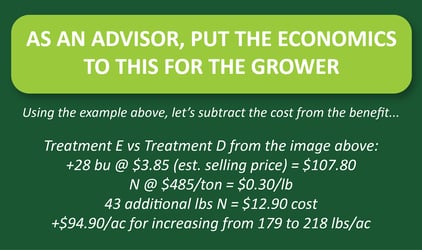

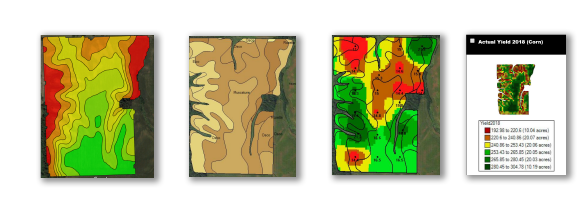

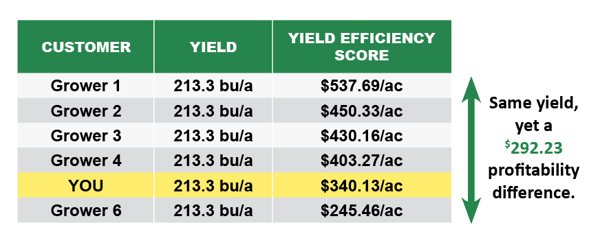

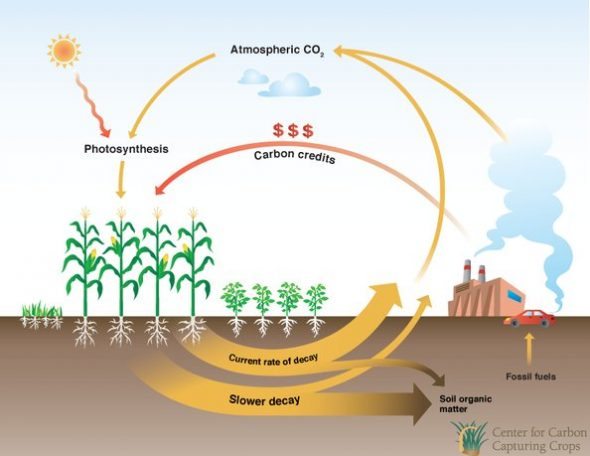

DAMIAN MASON: The future is two things: it’s specialization — a niche product — or it’s a commodity, big-scale commodity. But to your point, using your product: precision agricultural data analysis. More output per acre through good data, right? That’s what your product is. That’s what your company does. It helps a farm operator get more out of the inputs, the nutrients and the dollars that they put into each acre. They get out of it. What is probably going to happen with an environment of environmentalism — and this is only going to steep up, and I’m not getting into political stuff, but I keep up — certain forces that are political want to be more involved in agriculture, more of a thumb on us to be what we’re allowed to eat. Remember, there’s a certain young congresswoman from New York that preaches about cow farts and how there should be rations on how much burger we should be allowed to eat. So, if that’s the case, agriculture has a real opportunity. Your customers and your prospect of customers have a real opportunity here, Renee and Dan, to say: “Listen, here’s my environmental story. I took 10 percent of my most environmentally-sensitive acres out of production, and I enrolled them with the government conservation reserve program. And I could do that because my 90 percent more productive acres that are less environmentally sensitive are more maximized. In fact, I’m getting the exact same output off of all of my properties, all of my operation, as I did with 100 percent just with 90 percent because I am maximizing the output using better precision ag and data analysis and better practices.” That’s probably what we’re going to end up having to do. There will be less acres cultivated moving forward in the United States of America because of the environmental lobby, but also those lobbies, then, do tend to get government action. About two months ago, I got a solicitation from the government, NRCS, saying that if I had any land along a creek or river, I could put it in a 30-year conservation program. Now, up until now, Dan and Renee — you probably know this — it’s generally been a 10-year enrollment or maybe a 15-year enrollment. There is now a 30-year enrollment for certain environmentally-sensitive acres that also has rent escalators built in. Just like if I owned a shopping mall or a strip center, there would be rent bumps after a certain period of time. So, I think we’re going to see more of that. So, your pitch? Your company? I believe the angle is: “We help you get the most out of your great acres, so you can let your lesser acres revert to an environmental situation that, then, I can sell the environmental story.”

DAN FRIEBERG: Damian, a part of your business is really focused on audiences and meetings. So, how do you adapt? How do you adapt, and how soon do you think you’ll be back on the road?

DAMIAN MASON: Yeah, it’s tough because one of my big things I was talking about is reinvention, and I know you’ve got to always do what you can to stay relevant to your customers. You’ve got to meet them where they are, not where you are. That’s one of my big points to agriculture. Again, they’re at Whole Foods. They’re at farmer’s markets. They’re at the Kroger still, but they’re not there just saying: “How cheap? How cheap?” American agriculture tends to think that because we’re cheap, we think our customers are cheap or whatever. They think we value production and quantity and how many bushels per acre we think they do. Well, they don’t care. They don’t know what a bushel even is. They don’t know that at least 56 pounds for No. 2 yellow corn and all those kinds of things. I’ve got to meet my customers where they are. So, right now, my people still want me to deliver my commentary, my future, my outlook, my business ideas about the business of agriculture in a comedic fashion. I’m doing it sometimes on Zoom calls. I’m doing it virtually, and I’m doing less of it. We will get back to having live meetings because there is a human thing. An article in the Wall Street Journal yesterday talked about the “pandemic fatigue,” as much as the scared class wants everybody to stay home and stay scared. I’m sorry. Stay home and stay tuned. Oh, I’m sorry. Stay home and stay safe. See, that’s really what I think it is. The media needs you to stay tuned, so they can keep selling you crap on the TV. There is a “pandemic fatigue” that’s set in. People — humans — are social beings. They want to get together.

Their idea I hear is people saying: “We’re never going to have meetings again.” Well, the Marriott still thinks there’s going to be and the Hyatt and the Hilton and the Westin. And the other part of it is you can’t get drunk at the Marriott bar and complain about your boss on a Zoom call. You have to go and do that. So, the corporate audiences are still going to do that. That will come back. Will I do as many meetings, one year from now, as I used to do? Probably not, but we’re still going to do some online stuff, and I’ve got a few other ventures that I’m dabbling into because that’s the reality. You’ve got to move. You’ve got to change, and the more important thing is you’ve got to meet the customers where they are. I started by saying that with our recording, that we’re a consumer business. All businesses are. I tell everybody the best thing to remember is every dollar you’re going to make the rest of your life is someone else’s dollar right now. And so, be adaptive. It is a challenge. It’s been a challenge for me because, also, the rug got pulled out in a very quick fashion. We woke up on March 13th, and my wife said: “Did you check your email?” I said: “No, I’m making you coffee.” I had just gotten home the evening before from South Dakota. And she says: “The next five events are all canceled.” And then the next five after that, and the next five after that. So, the rug got pulled up pretty promptly, and that’s an extreme situation. My sister-in-law owns a gym with her husband, and their business got rocked. Imagine if you were in the movie theaters business. 7,800 movie theaters, according to an article I read — two-thirds of them might reopen. Think about that. One-third of movie theaters are never going to reopen, according to what the predictions are, maybe less. We’re all in a predicament, in terms of that. Now, the good thing about agriculture? Acres still get planted. In places like where you are, in Iowa, and Indiana, where I am, we get adequate precipitation. We still are probably going to be okay. We still have a certain demand. Our challenges are usually more about managing low prices and overproduction. That’s not all bad. It beats the heck out of the alternative, as we saw. We’re all dealing with some of the adaptations. I used to make a living dressed up as Bill Clinton, going to corporate events and standing on stage, saying: “How y’all doing? How y’all doing? I feel your pain. Hey, darling, let me show you what I do like to feel.” Anyway, I’ve made changes before to my career. It’s something that I’ve gotten accustomed to doing.

DAN FRIEBERG: Well, I think there could be a boom in meetings. I mean, just a pent-up boom because you go a year-and-a-half — or whatever we’re going to, a year — without it. I think people are going to be anxious to get back.

DAMIAN MASON: Now, I wondered that also. I said 2021. There’s enough scare, and I’m not altogether convinced that it’s pure. I think that there’s a certain amount of posturing and power grab going on to keep the electorate scared. But, yeah, what you’re talking about is pent-up demand, and there’s one thing we know about humans. They’re saying: “Oh, there’s pandemic fatigue.” Or: “Oh, I want to go see grandma.” Well, we’re worried about getting grandma sick. Well, grandma finally says: “I’m going to be dying in a nursing home. One of these days, I’d rather let my grandchildren come and see me at the risk that I get coronavirus.” So, there’s that reality. But you talk about pent-up demand. We’ve seen this before. In times of austerity, then, there’s that pendulum swinging back. You can remember this because we’re all old enough to remember this. There was a time when red meat consumption kept declining, and it was the scare tactics. It was probably not completely scientific. There was always a group. Remember, if there’s a crisis, there’s usually a group that’s profiting by perpetuating the crisis.

We were never going to eat steak again. And then, fast forward to things got really good. Remember the dot-coms and all that stuff? Late nineties? Every city in America opened up three new steakhouses, and I’m going: “Wait a minute. In the eighties, they told us we were never going to eat steak again.” Now, there’s a Sullivan’s and a Ruth’s Chris and this one in every town — Des Moines, Indianapolis, you name it. So, I’ve seen the pendulum swing before: austerity for very long, then, creates this thing where, then, people are like: “No. Done.” And then, it’s the other way around. So, you’re right. We could end up, by a year or so from now, with people like: “Screw it. I participated in the pandemic. I’ve been through enough Clorox wipes to fill a landfill. I’m going out, and I’m going to have us a meeting.” And there’s a human factor to that, guys. Your customers want to get together. Your employees probably would like to do that. So, there’s a human factor, too. There’s no question that people want that. I remember, after 9/11, I saw it. With 9/11, people did not want to get on a plane. They did not want to be in a building that was of any size. And then, eventually, they said: “I’m not going to live in fear.” Now, some still did, but not the bulk of the people. They said: “Yeah, we’re not going to live like this. I still want to be a human.”

RENEE HANSEN: That’s kind of the pendulum swing with commodity prices, too.

DAMIAN MASON: We saw the swing where, probably — and I’m not a grain marketing person. I got a C in Ag Econ 320, which was grain marketing. I find it to be hideously boring. I mean, if you give me economics stuff, consumer outlook stuff, that’s my real direction. Sitting and staring at a computer screen all day and then getting excited over a three-cent move in the soybean markets? I’ve pointed it out before. These people that do that? I’d have to have some sort of pile of drugs right here just to make my life interesting if I had to sit and look at a screen all day and manage three-cent moves in the soybean market. But, being that said that I’m not a commodities marketing guy, we just ran up 10 percent and 25 percent on the corn, right? You can sell corn for 25 percent more, roughly, than you could just in July, let’s say. How would you think that it’s going to go that much again? If it were me, and I had an operation to run, I’d be looking at trying to forward contract everything for next year, also, because a long time ago, somebody smart told me: “You don’t go broke. Your business doesn’t go under by taking profits.” So, I think that we’re probably where we’re going to be. Also, what fundamentals are going to change? Are we going to have another billion people on Earth? That’s been a prediction I’ve been hearing my whole life. No. Did the pandemic create a baby boom? No, actually divorce rates are up 34 percent. Divorce filings are up 34 percent in the United States. People didn’t stay home and make babies. They stayed home and decided they didn’t like each other.

So, we’re not going to have a population boom in the whole globe. In fact, for the next year, the economic devastation will cause us to eat less meat because in my book, “Food Fear,” I talk about this. The last time we saw meat declines in developed countries was during the recession between ‘08 and ‘12 to ‘14. Meat consumption went down by 10 percent here in the United States. If meat consumption goes down 10 percent here, what’s it doing to a lesser developed country, a country that’s more harmed economically by the pandemic, that didn’t have a government throw $6 trillion of relief at it? Let’s say their meat consumption goes, and they don’t eat but half of what we eat anyhow. Let’s say their meat consumption goes down by 20 percent, and they only eat half as much meat as us anyhow, but it’s a country like India, let’s say. Now, corn and soybeans become meat. If those countries are eating less meat, why would corn and soybean prices remain high? So, I believe that, if it were me and I was a commodity producer, I would take advantage of this marketplace to sell as much stuff forward as possible because I’m looking at it. Again, I’m an observer. Comedy taught me to be an observer. I know what meat consumption does, and I know these economic situations we’re living in right now. They keep saying a “V-shaped recovery.” We’ve been saying that since March. How can that be? A “V” doesn’t go from March until Halloween. I think that we’re going to have economic hardship, globally, for quite some time. Europe is shutting down right now, and take Europe as an example. In Ireland, you’re not allowed to leave your house and go more than three miles. People are saying: “Yeah, but why would that hurt meat consumption?” Well, beef, for instance — most beef is consumed away from the home, not in the home, and that’s in the United States. Presumably, it’s that way in Ireland, as well. That’s why meat consumption patterns are going to change a bit. That’s my observation. Every observation, I can give you a reason for “why,” the data behind it. That’s what I always tell everybody. You can disagree, but don’t think that I haven’t at least pulled the data.

RENEE HANSEN: Well, and I would agree. I do agree with that because you do. And you reference it a ton in your book, “Food Fear.” So, I’d love for our audience to check out Damian Mason’s book, titled “Food Fear.” And Damian, why don’t you just tell our audience how they can get ahold of you?

DAMIAN MASON: All right, they can go to damianmason.com. If they happen to be watching, it’s on the screen right behind me. But if they’re not watching, they’re just listening, it’s Damian: D-A-M-I-A-N. Damian Mason, like a bricklayer: damianmason.com. I’m on every social media format. That’s not true. I don’t do Tik Tok. I’m on Twitter. I’m on LinkedIn. I’m on Facebook. I got a fan page there. Check it out. I’ve got LinkedIn, the whole deal, but also my website. I put up videos on YouTube. You can go to YouTube, Damian Mason channel, and hit subscribe. And you’ll see the videos that I put out with various commentary and whatnot. I would love for you to do so, and I very much appreciate you having me on today.

RENEE HANSEN: Yes, we really appreciate your time today, too. Thank you so much for all of your information and trends and knowledge that you continue to share.

DAMIAN MASON: Thanks.

RENEE HANSEN: Thanks for listening to the Premier Podcast, where everything agronomic is economic. Please subscribe, rate and review this podcast, so we can continue to provide the best precision ag and analytic results for you. And to learn more about Premier Crop, visit our blog at premiercrop.com.

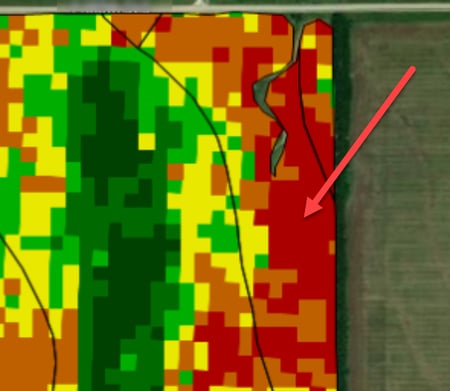

Image from

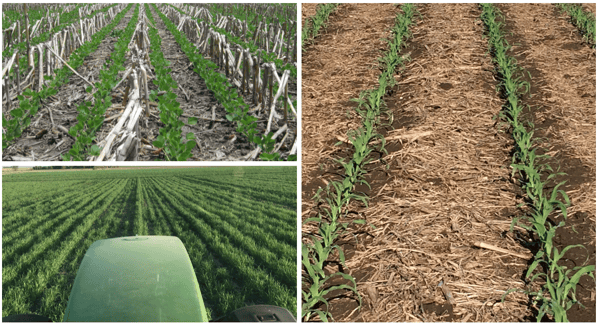

Image from  Upper Left: No-till; Lower Left: Cover Crop; Right: Row spacing

Upper Left: No-till; Lower Left: Cover Crop; Right: Row spacing