In our latest Premier Podcast:

“The more data you get,

the more it lets you break it apart

into more meaningful insights.”

– Dan Frieberg

DARREN FEHR: In today’s session, we’re going to talk about big data. I should start off with the definition of big data, so our listeners can get connected to what we’re talking about. It’s a phrase that has integrated this world of technology across industries. It’s about capturing relevant data from a huge number of sources, collecting it today and translating it into something that people can use, into actionable insights to solve problems at scale and at speed. In this world of ag, we have billions of dollars of venture capital funding pouring into agriculture through technology builds, and big data has been at the center of a lot of that. How do you see this being advantageous for agriculture?

DAN FRIEBERG: Darren, I think it depends on the lens that you’re looking through. If you’re a manufacturer, there’s probably a different set of values from big data than if you’re a grower. So, it probably depends on your goal. What do you want to accomplish with the data? Obviously, big data is enabled by computing power. We just have a lot more capacity because of server farms and cloud computing. We just have way more capacity, which lets us collect more and then lets us crunch through more data. In ag, it’s relatively recent. It’s not lost on me that, before yield monitors, we really made a lot of decisions in ag based on what I would call small data, which was a lot of replicated trials. And we’re talking tiny, where a replication in a trial might be 25-feet-long, replicated three times. That becomes an observation. So now, with yield monitors and all the other devices, we’re able to collect data at such high resolution. In a hundred-acre field, we would divide that field into 4,000 unique observations that are geo-referenced, tied with a lat, long, yield value and hundreds of layers of data underneath that.

DARREN FEHR: I want to get back to our big data collecting capabilities. There’s a ton of data being collected in ag today, from a lot of different sources, and a whole bunch of it is public. It seems like there’s a lot of these newer companies coming out, trying to take advantage of public data and the complexity of sourcing it and putting it together into some usable format. What are the benefits for the farmer, in terms of seeing all of the publicly available data and, specifically, for their farm and how it helps them make decisions?

DAN FRIEBERG: With a lot of the public data, for us, it’s really course. We would call it really course, meaning it’s not drilled down to a level where I think it’s all that helpful. But if you’re a company, and you’re selling an analytics package to a grain trading company, the truth is you don’t need it refined. That coarseness is fine because you’re trying to understand global yield trends and how it will move the supply chain. So, to me, a lot of the public sources aren’t as valuable to a grower as they are to other stakeholders.

DARREN FEHR: Let’s talk about some of the myths out there on big data, and this is one thing we hear a lot. We hear the words “weather modeling,” but what we’re talking about is predicting the future. It might be future weather or future performance. Tell me about big data in predicting the future. My understanding is it’s always been based on historical data, and if the historical data isn’t validated and verified at a high enough resolution, how do we use all of this to predict or model future production trends?

DAN FRIEBERG: All models are based on assumptions. They’re based on data, but there’s some assumption built into them. It’s about understanding specific geographies within fields, how they’re similar to other similar geographies in other fields. It’s almost like the more data you get, the more it lets you break it apart into more meaningful insights. The power of what we have in ag is that you have different growing environments every year. As we grow as a company, we have different growing environments within the same year. So, Nebraska or Minnesota can have a dramatically different growing environment than Indiana and Ohio. For example, you could see how a hybrid or variety performs in the same year in dramatically different growing environments, just because you’re seeing it across these big geographies.

DARREN FEHR: But that’s highly dependent on believing in this idea that agronomy is local, that agronomy and geography have a really close relationship with each other. There’s this whole idea of big data and aggregating it across multiple different agronomic environments. How do we give it enough credibility that people can make decisions from it?

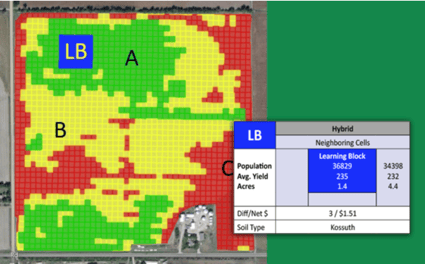

DAN FRIEBERG: Over the years, as we’re building as a company, the ability to aggregate data geographically is a big deal. The ultimate power of all this is subfield because that’s where you drive change. If you’re actually going to change and make improvements, it’s going to be subfield. Everybody wants to see beyond their own operation. They want to see agronomic practices or agronomic trends or rates. They want to see that beyond their own operation. As we’ve grown as a company, initially, when somebody comes in, they want to see the biggest data set possible, which means bigger geography. The bigger you get and the more data you get, then, all of a sudden, they’re like, “I really don’t care about seeing the big data. I want to see the local data.” Local is king in ag. The bigger, richer data set you can get locally, the more powerful it is because there are more things that are relevant and stay the same. We almost went through a decade where it seemed like the whole seed industry on corn was going to a lot of fixed-year numbers. The only way you could drive yield was to drive population. In the data, no matter what size of database, there was this trend. We were marching up 400 or 500 seeds per acre for a decade because that’s what it took in order to drive yields. Now, we’ve gone through almost a decade where it seems like there’s a lot of flex in numbers, so we’re producing much higher yields at lower populations. But, when we were going through that match up in population, all of a sudden people started looking at row width. We had this phenomenon where everybody was chasing 20-inch corn and even narrower corn. 39,000 in a 30-inch row is too close. The plants are on top of each other, and need to space them out more. In the data, 20-inch corn was a South Dakota and southern Minnesota phenomenon. That’s where we were seeing the most 20-inch corn. We had people outside of that area that wanted to drill down. They wanted to see data outside of their area because they were trying to make a decision about switching to a narrower row of corn, as a way to space out the plants as they continue to drive the population.

DARREN FEHR: With this idea of resolution, first of all, it’s data resolution. I want to make sure that we’re clear. You mentioned the word subfield, and to all our listeners, when I say high resolution, I’m meaning subfield. This goes beyond the field boundary, and we’re looking at different parts of different areas inside of every field. So, high-resolution data means subfield. I look at it like digital photography. We walk around with our cell phones, and they’re not phones anymore. They’re cameras, obviously. They’re used for filming and capturing videos. I always marvel at the fact that, when you capture a digital photo today, at a very high resolution, you can blow it up and make it as big as you want, and it’s still clear. I think about big data that way. If we capture and collect it at this subfield or high-resolution level, we can blow it up, and we can use it so that the insights are still clear.

DAN FRIEBERG: No matter how much you blow it up. Versus the other way. If you don’t capture that kind of detail, then, as you blow it up, it distorts.

DARREN FEHR: Myths about big data: if you haven’t got involved in big data now, you’re probably too late.

DAN FRIEBERG: No, not at all. A lot of growers are sitting on data, and nobody’s helped them use it. Yield data is, by far, the most. There are growers who quit caring about yield data because they haven’t used it. One of our successes is that, as we get engaged, we grab that historic yield data and try to use it to capture the variability that exists within fields. With a lot of growers, their data is in different buckets, and it’s not put together in a way that they really can capture it. A 3,000-acre grower in our system would create 120,000 observations. We would see yield by all these hundreds of layers of data, 120,000 times, just on a 3,000-acre operation. You can go from zero to big data really quick in farming. Anytime you get started is great, and you can start creating value right away.

DARREN FEHR: Another Big Data Myth: Data is messy, it’s complex, it can be confusing and it can be deceiving. Let’s talk about this idea where I see relationships between the data, which you have always talked to us about in terms of correlations, but not always do those relationships cause an effect. Talk about causation and correlation. As we think about this COVID-19 business, there’s an incredible amount of data being used to inform the public about what’s going on. Do we have the right metrics? Do we have the right data that is coming out, and do people understand the context of the data? What is safe and what’s not? Talk about your view on correlations here and how deceiving it can be.

DAN FRIEBERG: Well, just before we talk about COVID real quick, because we’re capturing data off the planter, as it goes across the field, we’ve been able to calculate planting speed. One of the very early signs was we had a report that showed the faster they planted the corn, the better and higher the yield. So, there’s a correlation. That’s an example where faster planting speed was correlated to higher yields, but when you actually interviewed the grower and talked to the grower about what happened in that field, parts of the field worked up rough. And so, they slowed down because they were trying to maintain seed-soil contact. As they went into those areas that worked up rough, they slowed the tractor down and slowed the planter down. In the part of the field that worked up great, they planted at normal speed or higher speed and, sure enough, that was where the higher yields were. The rougher areas worked up rough, so the real correlation was to field conditions of planting, but it showed up as planting speeds. So, it was an example where you can have correlation, but it doesn’t necessarily mean causation.

The COVID thing, Darren, is so wild from a data perspective, and I just feel like we are in the Wild West every time I watch the news. I think there’s way more exposure than what we realize just because of not testing as much. I saw a news clip last week where Rhode Island has the highest number of new cases per 100,000 people. Rhode Island is leading the nation. But then, you look at the other statistic, which is they’re doing way more testing. They’re leading the nation in testing per 100,000 people. The reason they’re leading the nation in new cases is they’re leading the nation in more tests. Clearly, with COVID, there’s a spatial piece to it, like the density of populations. We’re not immune in rural environments, but a whole bunch of people are rethinking living close to other people. We could actually have a migration to rural America because you’re not as packed in as tight as you are in big cities or, obviously, in any place we can find people, space-wise. There’s a big spatial piece to the COVID thing, and there’s going to be so much data analytics coming out of this when we get done. It’ll be interesting.

DARREN FEHR: Let’s talk about nitrogen and data. Nitrogen seems to be a very popular topic, and there’s always this idea that one pound of nitrogen is enough to produce a bushel of corn. Talk to me about this generalization of data.

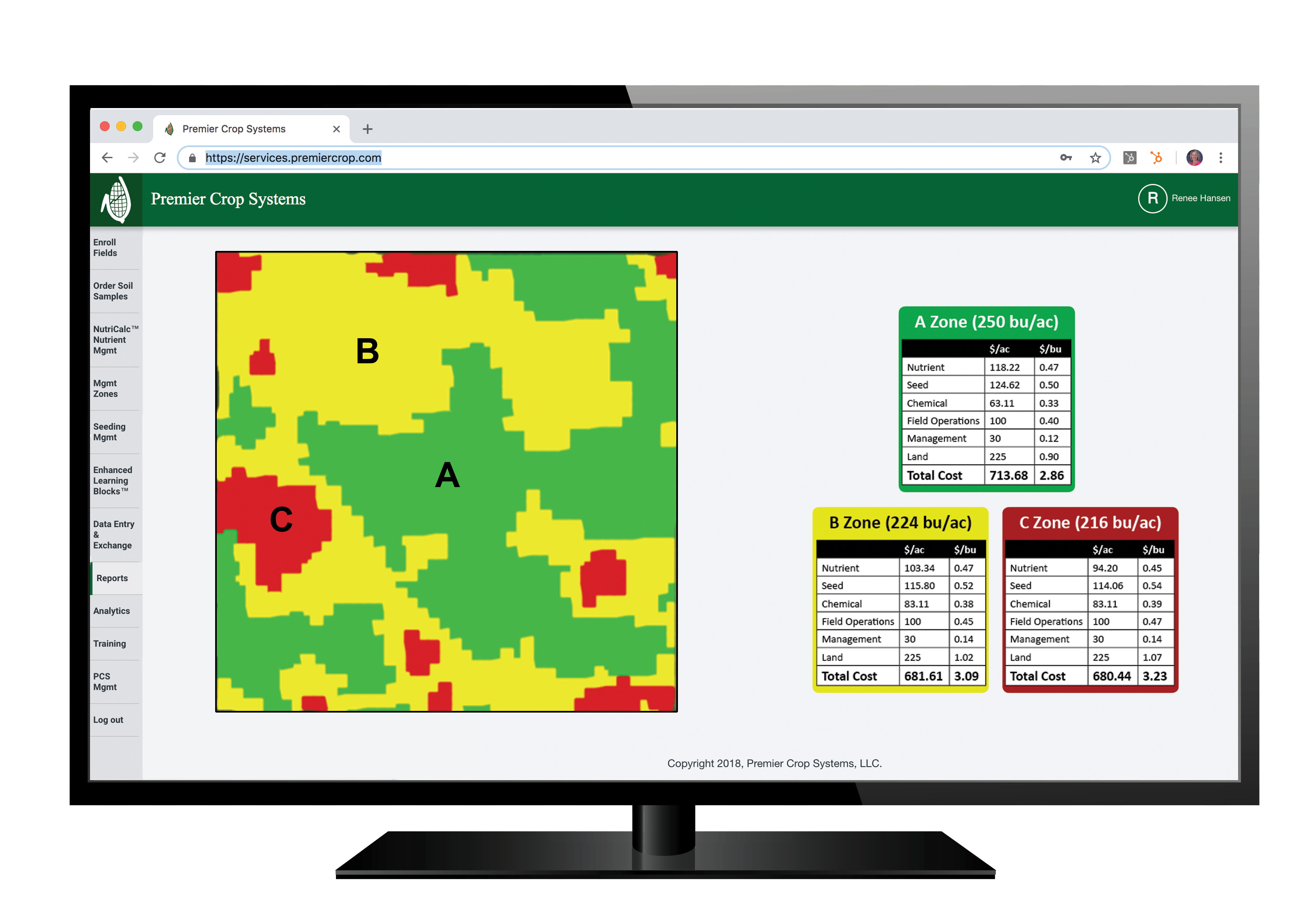

DAN FRIEBERG: That’s a historic number, so it’s not recent. Universities have all flipped, and that’s not the university recommendation now. For decades, we lived in a world of this idea of 1.2 pounds of nitrogen per bushel produced minus credits for legume. If you’re on a corn-soybean rotation with a 250-bushel yield goal, or 200, let’s say, 1.2 would be 240 minus 40 or 50 pounds of credit for a soybean crop per head. That would put you back at about 200 pounds of N. So, that 1.2 less credits led people to this notion of about a pound of nitrogen per bushel produced. Certainly, what our experience has been is that’s no longer at all close. Nitrogen use in the data, Darren, tends to fluctuate a lot with the price of commodities. I hate to say it, but when we went through a seven-dollar corn cycle, you could see it in N rates. Now that things are tight again, we’re back to what I think we should be all the time, which is trying to squeeze every bushel out of each pound of nutrient that we apply. So, I think we’re actually in a better place. In times like this, we’ve seen people produce plus 200-bushel yields on 0.6 pounds of N per bushel. That’s really scrutinizing your nitrogen and it’s using variable rate to do nitrogen. Growers want to make sure that nitrogen is not what’s yield limiting. They tend to be aggressive a lot of times, and so we try to help them put that in perspective. Actually, that idea of a pound of N per bushel may not be that far off, except that there are zones within a field where 0.7 pounds of N per bushel might be ideal. And there are other parts of the field where it might take more than a pound of N per bushel produced. We believe very much that nitrogen response is very spatial. It changes. The ideal rate changes within each field. Of all the nutrients, nitrogen would probably be the one that is the most uniformly applied. A lot of growers put the same rate on every acre, and so we see it as an opportunity for dramatic improvement.

DARREN FEHR: We are somewhat biased because we’ve been promoting variable rate technology for two decades. Seed population and planting population aren’t that much different. We’re biased because we see the incredible amount of dollars left on the table. Planting population, specifically in soybeans, have just taken a dramatic turn. Talk about that.

DAN FRIEBERG: Soybeans have just been the opposite strategy of corn. We keep backing off the population in the best parts of fields and seem to actually continue to increase yield. We probably hold our populations a little higher in the worst part of the field, just to be more aggressive in those defensive areas. There’s not as many dollars in play from a seed investment perspective, but we’re still seeing dramatic positive results from reducing populations, in almost any kind of a growing environment, as well. Last year, Darren, was the exception because we had so much late-planted. So, last year, because of 2019 being such a wet spring, we pushed soybean planting so late that it was probably the outlier in the data.

DARREN FEHR: What are some examples? You’ve done a lot of work on the economics of variable rate. What are some examples that you can think of that come to mind about just the shock and awe of how much money is left out there when we deploy flat-rate solutions?

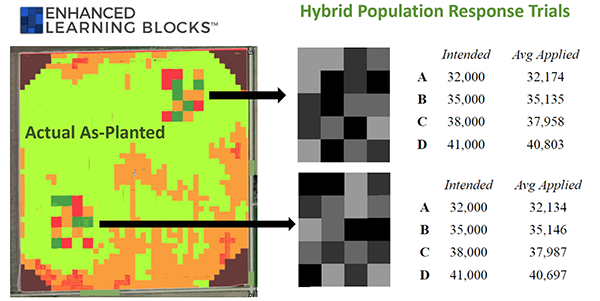

DAN FRIEBERG: We have the big data analytics, and we have all kinds of big data analytic tools, but now we’re able to do replicated trials in mass, in volume, in growers’ fields at the speed of farming. The equipment is executing the trial, so it’s preprogrammed. The trial is preprogrammed into the prescription, so we’re laying down replicated trials. We’re ramping up really fast, and then we can aggregate those trial results to like-agronomic environments. I’m a huge advocate of variable rate everything, but now we’re able to put the dollars and cents to it through replicated trials. And it really surprises me. We’re talking about 100-dollar-an-acre net swings for as little as a 4,000-seed difference. Just dramatic swings. So, if you push over the top, if you push populations too far, not only do you spend more on seed, but you can drive yields down really fast. Getting the rate right in every part of every field is big time dollars. On nitrogen, it could be 50-dollar, 60-dollar-an-acre swings. In this world that we’re in right now, when you talk about 50 to 100-dollars-an-acre differences, that’s it. We’re going into struggling to break even. We’re going to need some combination of crop insurance. Growers absolutely hate it, but we’re in a situation where, just to break even, we’re going to need some government program. There are all these political debates on how much to subsidize what part of the sector, but in the ag economy, it’s really difficult to make money, to break even. So, 50 to 100-dollar-an-acre swings, just on how you manage inputs, is real, and it’s big dollars.

DARREN FEHR: That’s a good setup for our next podcast, and that’s, all around, you can’t manage what you don’t measure. So, we’ll talk about that on our next podcast. Final words on how farmers should think about big data from your perspective?

DAN FRIEBERG: Big data needs local context. The best big data is local big data. That’s awesome, so that’s number one. Number two is that, instead of viewing big data as always providing the answers, sometimes I think the best thing about big data is providing the questions. Because big data lets you see relationships that you couldn’t see before, it sets you up to do a trial to answer the question. So, big data can be the source of what to look for next. It’s almost like, instead of providing answers, it provides the next question, which is what we’re all about: this continuous improvement. We’re all about: what can we do to change? What can we help you change to drive continuous improvement? With big data, sometimes it provides answers that you can take to the bank, but a lot of times it provides insights that lead to questions that lead to: let me do a trial. I think I see something, and now I want to prove it.

DARREN FEHR: That’s an incredible insight. Dan, it’s always a pleasure. It’s always fun to hear your thoughts, your experiences. Thanks for sharing your ideas and thoughts on big data.