“Squeezing every possible bushel and dollar out of every acre is critical. You have to create a farm plan to manage areas of your fields. It will produce a dramatically different productivity potential than those who don’t create a plan.”

DARREN FEHR: On a little more somber note, we’re coming off of a week that has seen some record devastation, some real problems. And first of all, first and foremost, on behalf of Premier Crop and all of us, I’m really, really sorry to see all of our farm friends and family go through this. Our hearts, minds and prayers go out to all those who have had such significant loss. Four dead: three in Iowa, one in Illinois. There were, 200,000 people without power for more than seven days, which is really, really difficult. I’ve heard something like 10 to 15 million acres damaged or written off completely. Some really serious devastation, and, even more than that, we have a grain storage problem with thousands of on-farm storage bins damaged or ruined completely. So, we have a fairly significant weather issue, and it kind of sets up the topic for today on creating a farm plan. And this is a question that we get often from either prospects or customers: why should I spend so much time planning when I can’t control the weather? Let’s just talk a little bit about that, about what goes into the resulting yield efficiency. How should we think about farm planning in light of the fact that, yes, we do not control the weather and we cannot predict the weather? So, what advice, Dan, do you have for our listeners?

DAN FRIEBERG: Sometimes, it’s best to tell a story or to paint a visual picture in people’s minds. This is one I have used over the years, and, as farm size gets larger, you may need to change the numbers. A lot of times, this is a dialogue with growers, and the question comes up, and what happens is they’re just so frustrated by an event like what happened. You have green snap, you have a wind event, you have hail, you have drought. There’s just this frustration, and I know that’s where it comes from and I understand the helplessness. I ask farmers and have them paint this picture: in your local area, in your local market, there are 160 acres that are coming up for sale. That’s 160 acres that is really uniform. It’s all one soil type. It’s been farmed for the last 30 years by the same operator. It’s been rotated as 160 acres for 30 years. In this case, it’s either been corn or soybean. Okay. So, it’s coming up for sale, and the auctioneer sells it, initially, as a 160-acre track, but then, sometimes, they will divide the track. They offer it as two 80s, and, sure enough, when they split it up and offer it as two 80s, it goes for a much higher price as two 80s than it did for the 160.

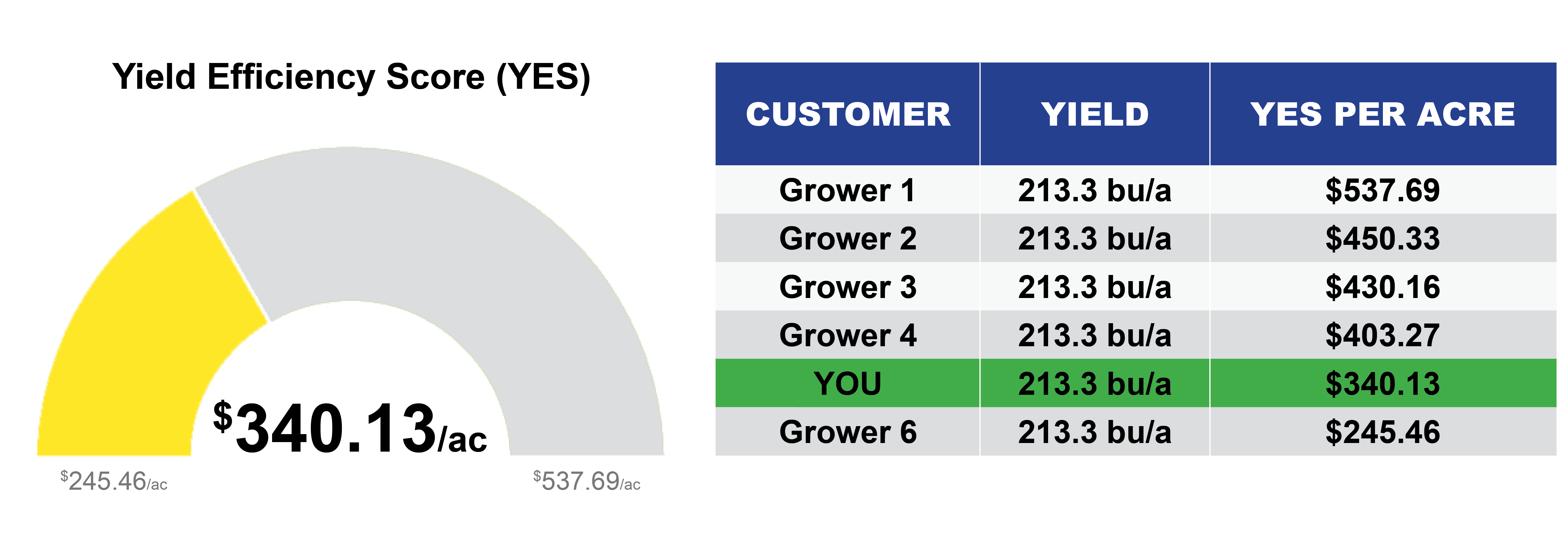

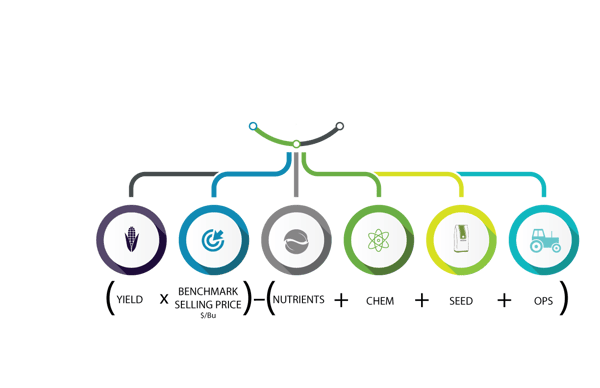

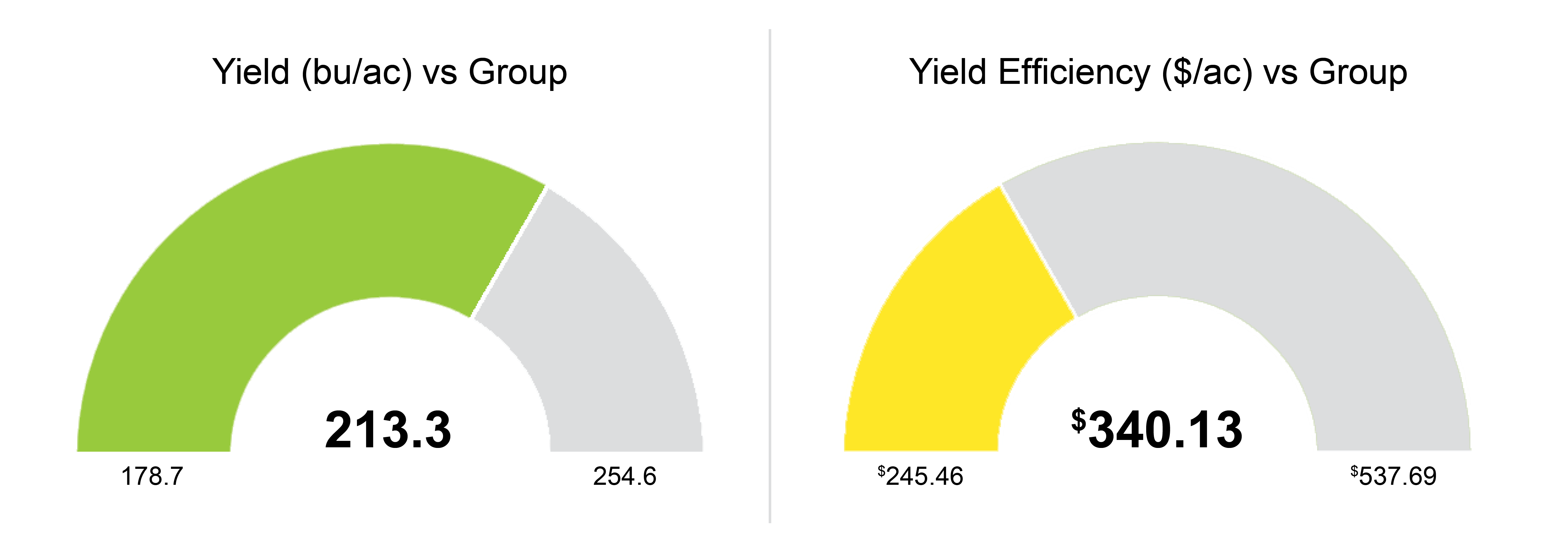

I ask the growers that I’m talking to: how much yield difference, or you could say how much yield efficiency difference, could there be between the two 80s? What I’ve done is I’ve basically said: this is uniform. It’s been farmed the same, and, because it’s a 160 acre field, those two growers are going to experience the exact same weather events. So, I ask them how much yield difference could there be? In the case of corn, it’s a 30 or 40-bushel difference, so think about that. If there could be 30 or 40-bushel differences, you’re talking more than a $150-an-acre swing in yield efficiency. The whole point of that exercise is, in everybody’s heads, they know that management matters. No matter what the weather, the details that go into farming really do matter. The management decisions that each of those growers makes, that’s where all the profit is. Details matter. Management matters. That’s what we’re all about. Farm Management matters, and having a farm plan matters no matter what the situation is.

DARREN FEHR: We’ve seen that time and time again, where our customers are constantly in the top 10 percent of the performance in their counties, for example, where, typically, you’d see some similar climatic conditions. Where management is intensified, or where we get this behavior of professional farming, you have the ability to make a difference. How do we approach farm planning, knowing that we can’t control the weather? What should we plan for, in terms of environment? If we talk about genetics and environment and management, there’s a management piece as a component, which we do a lot to help with, in terms of managing right-rate technology. But how should we approach weather in terms of: Am I planning for a dry year? Am I planning for a wet year? Am I planning for a 15-year average? What do you say about what should be the lens?

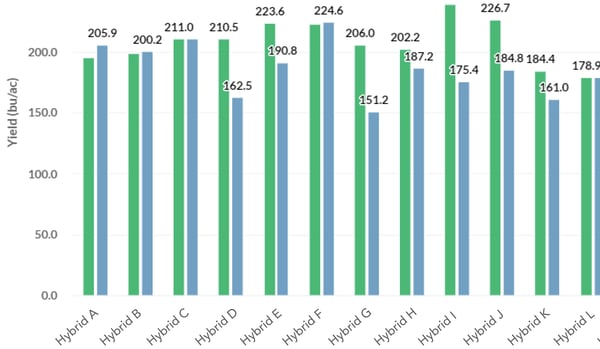

DAN FRIEBERG: So much of planning and, really, so much of the way people farm is about managing risk. A lot of the decisions are risk management. It tends to be very individual. Some people’s tolerance for risk is much greater. And how that plays out agronomically is, if your tolerance for risk is greater, you might be more aggressive in the way you plan and the decisions you make. And if your tolerance for risk is less, that could just be the financial constraints you’re under. When you’re under financial constraints, sometimes, you have to be a little bit more conservative. For example: hybrid selection. If you’re more conservative, you might deliberately choose hybrids that have a lot of flex. By choosing flex, it allows you to deal with the diversity of weather that you might experience. It would let you plant at a lower population. So, in a dry year, you have a lower population. You’re better able to handle the moisture stress. And in a wet year, if it’s wet, you have a little bit more potential for the hybrid to flex versus you know, when you make that choice, you could be choosing to give up the top end. There may be a racehorse that is capable of hitting the very highest yield for your area, and you may have passed on that, but you passed on it because you’re managing risk in a more conservative way versus somebody who’s maybe more aggressive. They might go the opposite, and they go out and pick the very highest-yielding numbers and plant them on a percent of their acres, just because they’re allowed to be more aggressive.

DARREN FEHR: I want to dig into soil fertility a little. You’ve been a soil fertility expert for many, many years.

DAN FRIEBERG: I’m kind of more of a practitioner, just somebody that’s had the luxury. I’ve had the luxury of seeing lots and lots of data.

DARREN FEHR: You have had the luxury of experimenting with other people’s farms and seeing terrific results of all experimentation, which is fantastic.

DAN FRIEBERG: It has been fun. That is what’s really fun about all this. You see all this going on in the data, but then you’re able to actually put down a trial or an experiment and follow through and see the results. So, it’s really been fun that way.

DARREN FEHR: Which is such a big reason why we’re so passionate about what we do. It’s because we see the results and the reality of it, but, on a soil fertility level, we’ve seen it time and time again. We’ve gone through weather events, whether it’s drought or flooding, and where we have established really strong long-term soil fertility principles, we have seen it time and time again. Our customers go through that easier or with better performance than others. Why?

DAN FRIEBERG: I think what you’re speaking to is when the weather turns against us, and that could be dry because we’ve got areas that have drier weather. So, when the weather turns against us, I think that’s when the reward for having a farm plan and managed fertility really pays, whatever that weather event is. I think we see more response to having that long-term fertility management in stress years than we do great years. I mean, when everything’s perfect weather-wise, you still see it in data, but I don’t think it’s quite as dramatic as it is in a stress year.

DARREN FEHR: A farm plan is almost like an unseen insurance policy, to some extent. It’s not going to save you, but it’s certainly not going to let you get as severe as others.

DAN FRIEBERG: It is. That’s exactly what it is.

DARREN FEHR: I think that’s the premise of this farm planning piece, that we can’t save our way to prosperity. We know that. This game isn’t about cutting costs. It’s about managing costs. And when we talk about farm planning, we’re talking about managing costs, managing resources in a way that we’re allocating them to the areas that can return the greatest. And we’re managing risk in areas where we know that productivity has historically been low.

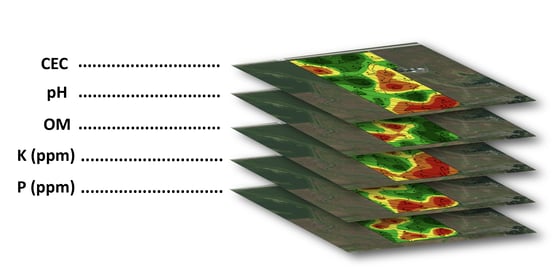

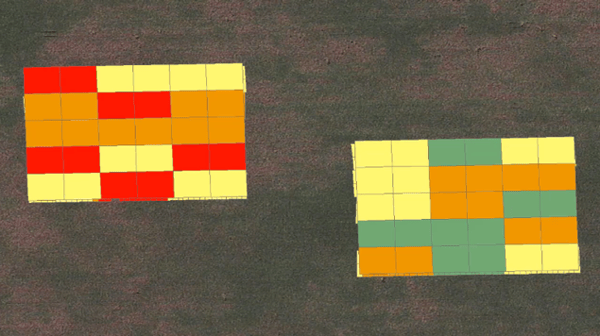

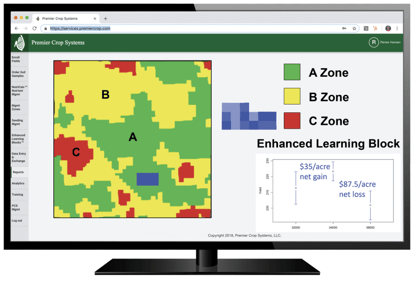

DAN FRIEBERG: Sometimes, I get challenged because of what we do, like you’re programming the field on how to behave. You are literally telling the field how to behave. Well, yeah, we’re doing it, but it’s based on data. It’s based on how the field has behaved, and then we constantly challenge ourselves. We put check blocks inside learning blocks inside prescriptions, just constantly to validate if we’re missing something, to make sure we don’t make a mistake in how we program the field. To me, this weather piece of planning has everything to do with it. There’s a lot of growers who are sitting on a mountain of historic yield data, and they haven’t necessarily used it very effectively. And to me, that’s a great starting place. It’s just a great way to get started and to use your historic yield data, to identify. It’s part of setting realistic yield expectations because it starts to let you know what’s the best it’s ever done. It’s just having realistic yield expectations for every part of it. There are areas that people farm that are never going to produce at the highest level. Then, it’s just about managing way more conservatively in those areas.

DARREN FEHR: You made a comment to me several years back: sometimes, it’s not even what you buy. It’s where you put it and how much you put on. I believe that the products that you use matter. I believe that we should plan before we buy.

DAN FRIEBERG: Everything works somewhere. Nothing works everywhere.

DARREN FEHR: Right on.

DAN FRIEBERG: Farmers are just bombarded by all kinds of new products: yield enhancers or efficiency this or that. It’s just constant. It’s microbials and stimulants and seed treatment. They all work in some place. Otherwise, they wouldn’t have found their way to the market, but they don’t work everywhere. I’ll guarantee you that. There’s something else that’s more yield limiting than whatever they’re fixing. So, figuring out what works where and at what rate is just the magic that we’re all chasing.

DARREN FEHR: One last point: Farm planning spatially versus at a field level. Pros and cons?

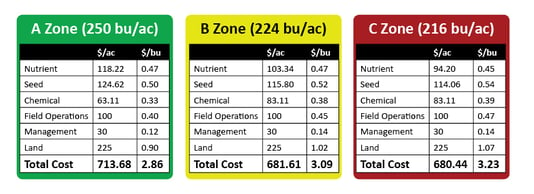

DAN FRIEBERG: Darren, there are operations that treat thousands of acres the same. They literally do everything exactly the same on every acre. So, going to a field level is a great start for them. It’s finally starting to acknowledge that there are differences within fields. That’s a great start, but, for us, it’s way deeper than that. Squeezing every possible bushel and dollar out of every acre is just critical. We think where this obviously leads is managing and creating a farm plan within fields, within areas of fields that have dramatically different productivity potential.

DARREN FEHR: Yeah, and just for our listeners’ perspective, we were literally managing every 20 by 30-foot area inside of every field and looking at them uniquely, looking at them as it could be different. And if it is, we would do something different in that small area of that field.

DAN FRIEBERG: It’s all within the equipment restraints. We’re realists. We kind of know the constraints of the equipment as it goes across the field and what it’s capable of executing on.

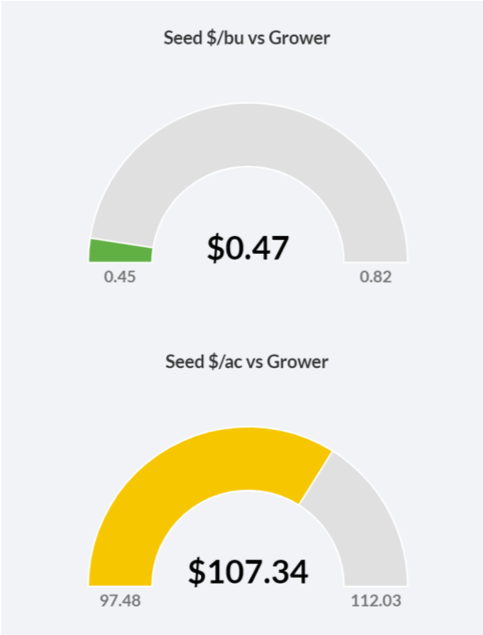

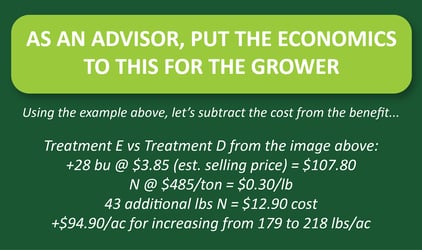

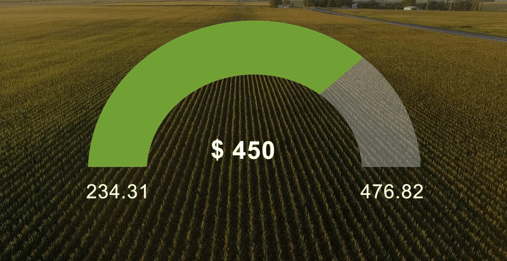

DARREN FEHR: When we think about applying our right-rate technology to farm planning versus field-level planning, how much money is at stake? Is it worth it? Is the hill worth the climb?

DAN FRIEBERG: It sure is. It’s not hard, in data, to find 100-dollar-an-acre swings. You think about where we’re at today. 100 dollars an acre is just gigantic. It’s easy to find individual decisions that amount to 100-dollar-an-acre swings. There are hundreds of dollars an acre differences.

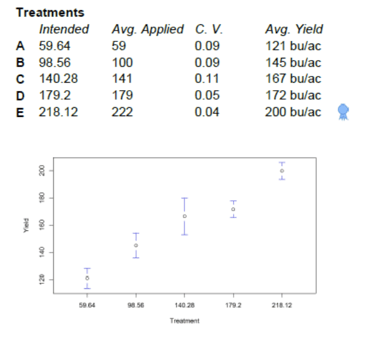

DARREN FEHR: It’s a huge deal, and farm planning without proving the result doesn’t really do us any good because we can’t really tell how effective our farm plan is. Something that we do very well is prove that the prescription pays or prove that the farm plan pays.

DAN FRIEBERG: Just that constant analyzing what you did, making sure. We analyze, and then we turn that into advice, and that advice could be anything related to how you make management decisions or agronomic decisions. That advice turns into action. The action, many times, is driving differences in how we treat pieces of fields. It’s just a continuous cycle. It’s all about shared learning and continuous improvement.

DARREN FEHR: We’ll keep talking about creating a farm plan and yield efficiency in our upcoming podcasts. Dan, thanks for being here. I hope you have a fantastic birthday. For anybody who wants more information on farm planning and proving your plan pays, you can get a hold of us at www.premiercrop.com. Thanks for being with us today.