“Data is valuable, but data in the hands of the right people with the right context is really, really valuable.” – T.J. Masker

RENEE HANSEN: You are listening to the Premier Podcast, where everything agronomic is economic. Today, we are talking with T.J. Masker, Senior Product Manager at Tractor Zoom, headquartered in Urbandale, Iowa. They are focused on helping bring price transparency to farm equipment and valuations for farmers, bankers, equipment dealers and insurance companies. T.J. has a lot of experience and knowledge in the precision ag space, and today, I asked him questions on how to unlock new insights to your farming operation using precision ag. Hey, T.J., welcome to the Premier Podcast. Just wanted to talk to you a little bit about unlocking some of the new insights to a farming operation, and I know you have a lot of experience. So, can you tell us a little bit about your background?

T.J. MASKER: Yeah, I grew up on a small family farm in southwest Iowa and did the traditional thing. Went to Iowa State, got an ag business degree, but for the last, well, about 11 years of my career, I’ve been working directly with farmers, helping them manage and understand their data better. So, whether that be agronomic data like soil tests, machine data that we get around like fuel usage or, in my current role helping farmers really value farm equipment, as that’s becoming the second highest cost on the balance sheet. What we’re really trying to understand is how we can make better decisions from that data. But the common theme is that ever since I went to Iowa State and graduated college, I’ve been passionate about helping farmers with data to make better decisions.

RENEE HANSEN: Yeah, you’ve had a lot of experience with data since you’ve been working in the field. So, can you tell me that? What is your experience with other precision ag systems, and what makes data so important?

T.J. MASKER: Yeah, I remember this, probably, like it was yesterday. I was covering a territory in south-central Iowa for one of the major seed brands. And I had farmers who kept asking me, like: ‘What can we do with this data? How do we start to think about how we utilize it more?’ This was almost eight years ago, and I literally Googled, like, ‘farm data’ something or another, and it led me, ironically enough, to Premier Crop and filled out the ‘contact us’ button. Then, I think it was Tony or Ben or somebody who reached out to me about: ‘Hey, we’d love to talk to you, understand where you’re coming from.’ And that ultimately led me to working with Premier Crop about seven-and-a-half years ago and doing direct advising with farmers in central Iowa. And many of those farms that I worked with back in the day, I’m still really close with today as I’m trying to solve new and unique problems, but I think, at that time, I had zero experience with precision ag. So, I had to learn how to set up the monitors, what Ag Leader SMS was, what software was to make better decisions. It was also my job to go out and recruit farms and help their operation. So, I think, over that time, I had to learn a tremendous amount about precision ag, what it was capable of. But, ultimately, I think for me, what it came down to is there’s so much value in this data and what we can get out of it if we’re measuring things correctly. And I think one of the things I experienced, even with the farms that have been collecting data for 15 years, was that, man, if we get this data structured in a way, it’s going to allow us to unlock so much potential. And whether that be if you’re using Climate FieldView or using John Deere Ops Center or using Granular, where I was at. It doesn’t matter unless the data is structured in a way that you can get the results out of it. And that, to me, was always the biggest ‘light bulb moment’ for a lot of the farmers.

RENEE HANSEN: Yeah, so since you’ve had the experience working with multiple different systems, what makes a specific platform better than another?

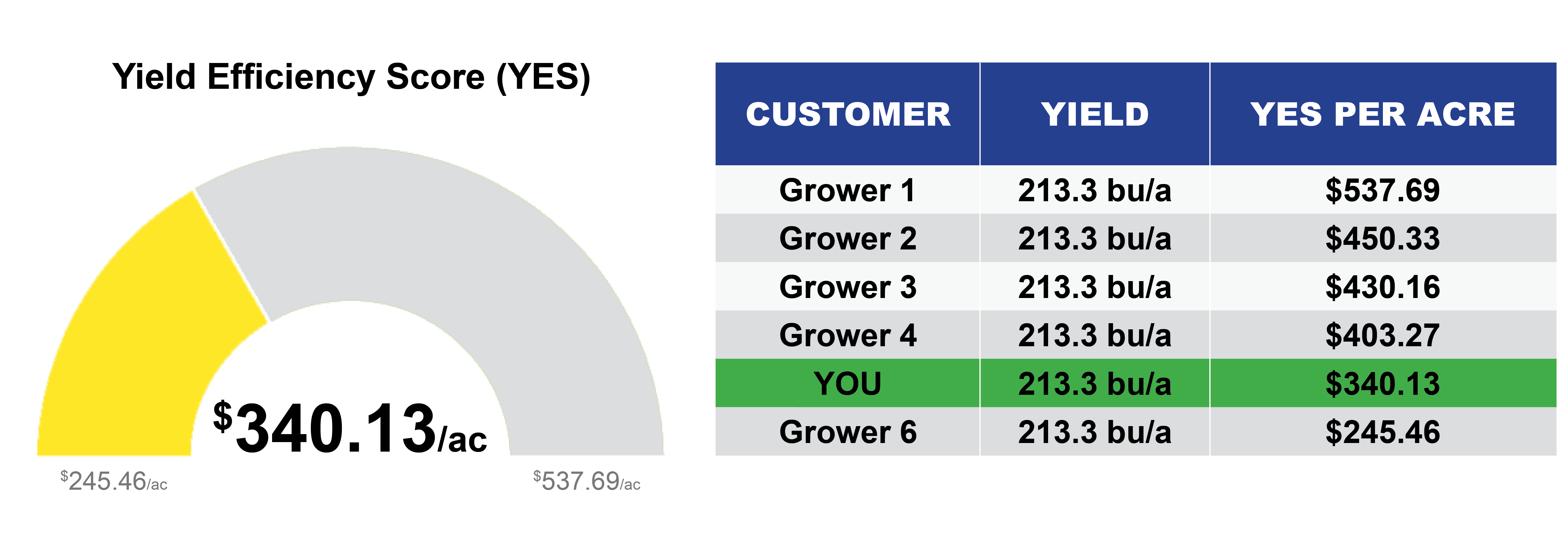

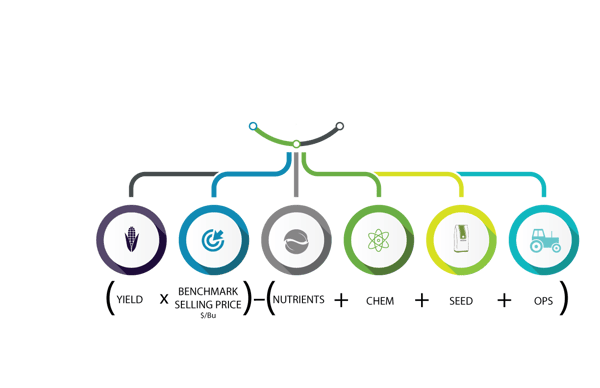

T.J. MASKER: When I talk to farmers about it, it’s really measuring the ROI, I think. Dan, I probably coined his phrase too, but if every agronomic decision is an economic decision, and we think about things that way, it fundamentally changes why we might do something. So, I think about systems that are able to actually provide that value to you as a farmer, and there’s not a ton of them out there. But we also need those systems that allow us to move data more easily. So, that’s why Climate, John Deere Ops Center, Ag Leader AgFiniti is another great example. Those tools help us get the data from the farm into the trusted advisor or the partner’s hands really quickly to make better decisions. That is valuable. I can tell you that there’s a reason why those tools are so heavily used because it solves a pain point. What I like to think about is: that’s one step. The next step is taking all this data and turning it into a better plan for next year. So, if I was at Granular, the way I described this problem is like: ‘I need to understand what we did and then how we did to understand what we need to do differently next year.’ So, if you focus on farmers collecting all this data on what they did, let’s get the scorecard for how they did at the end of the year. So, tools like Premier Crop. You think about all the things you can do with the query tool to answer questions from your data. Then, the real power is like: ‘All right. Using all this data, I now know with a high level of confidence going into next year that I’m going to have the best possible plan I can have.’ Mother Nature and God willing, things are going to fall into place. Well, let’s use everything we’ve learned to come up with the best possible plan, and we’ll adjust in season, right? Planting could get delayed by two weeks, so we might have to adjust seeding rates. All those things come into play, but let’s start with the best possible plan. And I think that starts with collecting and analyzing really great data throughout the previous growing season or previous seasons if you will, if you think about how many years of data a farm might have.

RENEE HANSEN: Yeah, I think you said something in there, like competence, where a grower just really needs to have that competence within the data. They’re collecting so much of it anyway. So, getting a grower started, it seems really overwhelming sometimes, just to get started with data because of the systems that you mentioned. They have Climate. They’re using John Deere Ops. Then, to add another system to their whole platform can seem really overwhelming.

T.J. MASKER: What’s funny is I’ve done customer discovery the last seven-plus years in my different product roles, and if you talk to every farmer, they’ll tell you they just want one system to manage everything. And the reality is that’s not possible. I think what we need to do as an industry to be better is to make things connected more easily, and you’re starting to see that. And the easier we can make it to connect different parts of the puzzle to the key people that need it, that is where you really drive value for the farmer. Because if you think about all the trusted people that the farmer is working for, you’ve got agronomists. You’ve got an equipment dealer. You’ve got a seed rep. You’ve got a banker. You’ve got probably a commodity broker advisor, potentially. So, you start to see all of these people that are helping the farmer with all the information that they have. It becomes really powerful if you can connect all those dots, and I think, for a while, we as an ag industry or a tech industry didn’t do a good job of this. I think everyone was trying to build a complete way to solve every problem. And now you’re starting to see that change quite a bit, and I believe it’s for the better because the more connected these things are, and the less you can alleviate a lot of the pain of getting data from one spot to another, the better off everyone’s going to be.

RENEE HANSEN: In one of our previous podcasts, we talked about how you need to connect all the pieces of the puzzle, and it sounds exactly what you’re talking about. You just need to connect everything together. It’s one big puzzle, and when you finally get it together, it starts to work like it’s more of a system. Growers have all this information. They have these systems. They have monitors. They have the tractors, like you said, that they’re heavily invested in. So, why would they invest in a service that helps them manage their data, that helps them make better decisions? Why should they do that?

T.J. MASKER: Yeah, I think this is really important, and I think understanding who you’re partnering with is really important too, from a farmer perspective. So, I think you’re going to see a lot of the bigger ag companies continue to invest in this space for good reason, right? They know there’s a tremendous amount of value in this data. What I also think is extremely valuable is what that independent advisor can mean to your farm. For example, I was out at one of the farms I used to work with on Friday, and we talked a lot about this. If you think about 7-8 years ago, where they were at, they were trying to manage it in house. They were writing their own fertilizer recommendations. They were collecting all their data. And now, fundamentally, they’re approaching things differently, and every year they’re trying to chip away at this thing. So, a great example is when I started working with them 7½-8 years ago. We talked a lot about: ‘Wow, you guys can grow really great soybeans. What if we grew more soybeans, for example?’ It was funny to talk with them on Friday. And as they approach planting season this year, they’re going to start one planter on corn and one planter on soybeans at the same time because the data has shown them that if they get in earlier on soybeans and get those soybeans in, there is X-yield gain from that. And that wouldn’t have been the case seven-and-a-half years ago. What data allows us to do is to test little things, and the way I always approached it with farmers was like: ‘Give it three years.’ We have the data that tells us that this decision is likely to produce a positive outcome. If we try it, we can’t just try it for one year. We have to commit to trying it for three because odds are, over those three years, we’re going to see that return. So, I think that’s where the power of having a system or a service to manage that is critically important. And I think you’re starting to see a few others come up in this space, as well, because they probably realize a little bit of the model of that trusted advisor is the most powerful model. And it’s because, fundamentally — again, I think Dan will probably laugh — but agronomy is local. What works for the Des Moines Lobe might not work as well where I’m from in southwest Iowa. It might not work as well for my buddy that farms in eastern Iowa. Data’s valuable, but data in the hands of the right people with the right context is really, really valuable. I think a lot of farmers are frustrated with managing that data. So, how do you find somebody that can help you and kind of provide that ROI? And, at the end of the day, they have to prove their worth, right? Fundamentally, they have to prove their worth, but I think they’d be surprised what they would see from partnering with somebody like that.

RENEE HANSEN: Yeah, definitely. Like what you said, there is definitely a shift that you’re starting to see with farmers, that they are wanting to see more of their data and utilize more of their data, where in the past, there was a lot of resistance and maybe because the market was too flooded. So, what would you tell a farmer who has resistance to working with a precision ag service?

T.J. MASKER: Once, I think I called on a farm for three straight months that was resistant to this, and it wasn’t because they didn’t see the value. It was that this was a piece of their operation that was so important to them that they’d been trying to figure out. And I think one of the things is when you have a group that’s been around for, let’s say, 15-20 years, there’s a lot of value in that versus I might be a little bit more skeptical of somebody that’s only been around a year or two because there’s that track record there. So, what I would think about looking at is who has a track record? Do they have farmers that are willing to talk to them about why they decided to partner with this person? Because, at the end of the day, we know there’s value in the data, but maybe there’s an opportunity for a farmer to share their story with another farmer that’s a little bit resistant and tell them: ‘Hey, I was exactly where you were at seven years ago, and now the way we do things seven years later is fundamentally different.’ So, I would just be open to having that conversation with others that are finding success in this area and help them along in their journey.

RENEE HANSEN: Well, sometimes, you get in a pattern where you are very comfortable with what you’ve been doing the past years, and you’ve been successful. You’ve been profitable, but there comes a point where there’s a tipping point where your margins are starting to get a lot thinner, and a grower needs to maybe change some practices. And that data can tell you exactly what practices to change.

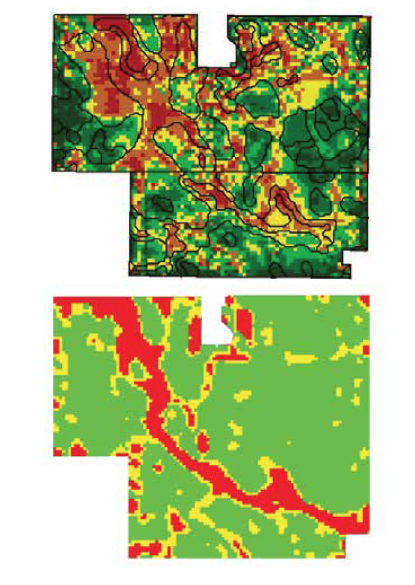

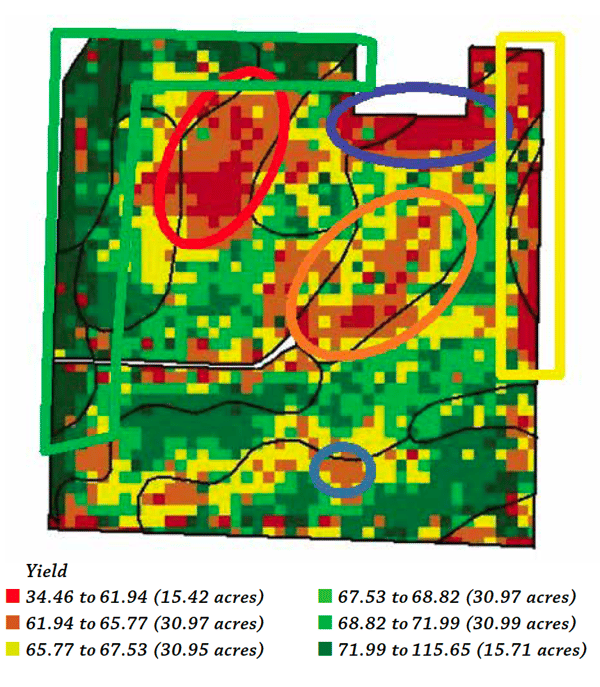

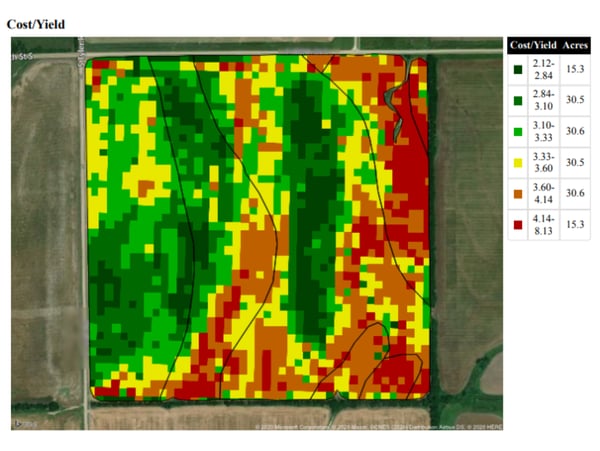

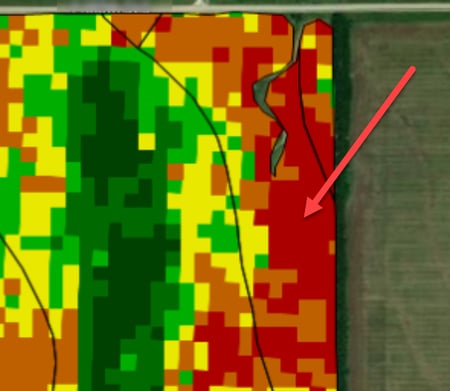

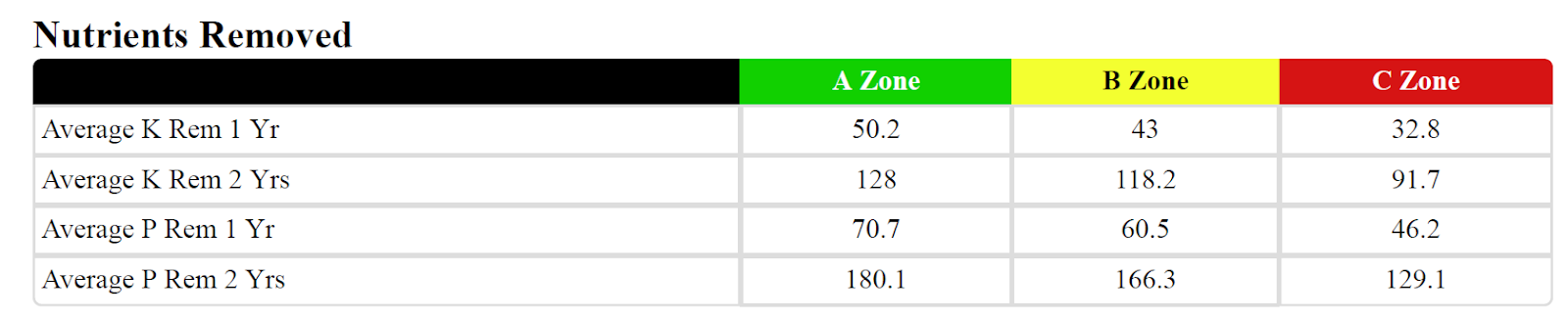

T.J. MASKER: Yeah, it definitely can. I mean, all these things come flooding back to my head, but you think about some of the marginal areas of your farm that just don’t produce much. We did the math 5-6 years ago, and it said: ‘Hey, if we don’t apply dry fertilizer on these spots, we can save an average of $5 an acre across all the acres.’ And the reason why we weren’t going to apply there is: one, we didn’t expect the return, and two, guess what? When we analyzed the soil test results by those areas, they were, a lot of times, the highest soil test values, which, if you back away from it, makes a ton of sense. Because if you’re applying the same rate of fertilizer across the field, and the good parts are taking off more, you’re going to see these lower-yielding spots, for example, have higher soil tests. So, you start to tell that story, and all of a sudden, you’re like: ‘Wow, just by doing that one thing, I’ve saved $5 an acre across all my acres.’ I don’t know what fertilizer prices are at today. Normally, I’d have a better pulse on it, but it might be higher. It might be $6-$7. I don’t know. But you start to approach things from that standpoint and manage each field like it’s its own kind of factory. I know there’s that analogy out there, but it really does make sense when you start to look at it at that level.

RENEE HANSEN: And a lot of companies are talking about data science and machine learning, and they’re trendy words. I don’t want farmers to get afraid of companies starting to use this because if they are resistant to using precision ag, they’re going to think: ‘Oh, well, now they’re just turning this into something that’s more automated.’ So, what do you think companies mean, and what should a farmer know about data science and machine learning within the precision ag space?

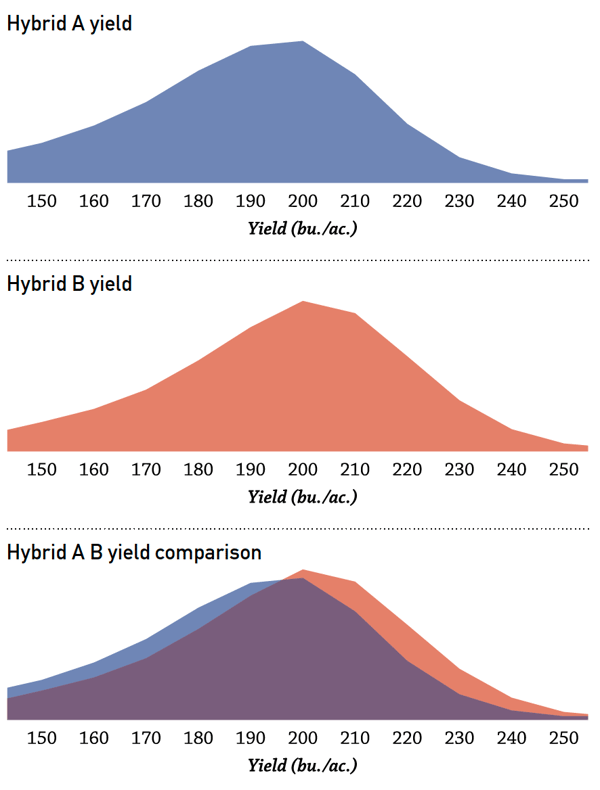

T.J. MASKER: Yeah, so companies are investing a lot of money into data science, and it’s an ability to take a lot of the data we have and try to learn really quickly. Versus a traditional method would be: ‘I’m going to evaluate this year’s crop. Then, I’m going to go around and, then, implement three practices that I learned from this year’s crop.’ Versus: ‘Hey, could we speed this up through data science and machine learning and try to learn from 15 crops and apply that knowledge to one year?’ What I will tell you is that most farms that I’ve worked with, and I still believe this to be the case today, is that they want to learn from the data on their own farm, but that also means that they can leverage data science on their own farm. So, the way I would think about it is to think about trials that you’re running. How are you setting them up? Because that truly is data science in its very, very simplistic form, but that’s what it is. We’re trying to test and validate things and use the data. Another trend, like with machine learning, is you’re going to hear more and more about ‘combine automation,’ which is real. I think I was listening to a podcast the other week about how they go out to a farm and demonstrate this to a farmer. Because most people would say: ‘Hey, I know I can adjust the settings on my combine better than any computer can.’ So, one of the things they do is they completely purposely set the settings wrong on the combine for one pass, push the button and watch it adjust. And they watch the farmers’ eyes light up with how quickly and how accurate those adjustments are, and I’ll tell you the tech side of things. As I’ve been talking to farmers specifically about equipment, the tech side of things is tying more and more into that equipment-buying decision. So, what technology are you using? Who’s the provider, whether it be John Deere or Case, or what’s the system that’s going to manage it? And they’re starting to talk more about making decisions for new combines based on automation, which is machine learning which taught that. I think you saw some announcements from John Deere in the last two weeks with the See & Spray technology with the acquisition of Blue River. So, this stuff is going to keep coming, and it’s going to come pretty fast. But at the end of the day, it’s just like a trial on the farm, where seeing is believing. And I think once you see this technology in the hands of different people, you’re going to see people adopt it at different rates, but I’m pretty bullish on the ‘combine automation’ stuff just because of what I’ve seen and what it can do. And I know, from direct feedback from 50-plus farmers over the last four weeks, that is something that they’re looking at.

RENEE HANSEN: Yeah, it’s pretty incredible, the advancements that they’re making within the technology, just with the tractors, the combines. But, then, also kind of going back to that data, too, and data science, where if a grower is anywhat interested in their data, having to layer all of that in a spreadsheet of Excel and having your brain trying to figure it out, it’s just too difficult. Let the computer do the mathematics for you. I mean, that’s the whole purpose of the data science. It’s learning through your data. So, I’m just kind of reiterating what you were saying, T.J. You’ve shared a couple of stories. You shared that you talked with 50 farmers within the last four weeks. What are some of the most successful stories that you have from a farmer using precision ag?

T.J. MASKER: Yeah, I remember this was kind of the fun one and like the best case study that I have. It was that we started working on a problem, and the same thing applies to product management if I’m trying to solve a problem for a farmer. But it’s like: ‘What’s the goal here?’ And it’s like: ‘The goal was to increase soybean yields for this specific farm.’ They couldn’t get above 45 bushels. So, we started to break down the problem and study the group data that we had, to say, okay, well, we haven’t ‘limed’ in five years. Maybe that’s something we could do. Another thing that the farm hadn’t done in five years was try a different seed brand or variety. So, that’s another thing we could do. Another thing they typically did was only fertilized ahead of the corn crop. Okay. So, let’s split up that application. So, we literally picked a field and said: ‘We’re going to kitchen sink it, and we’re going to try everything we can. And we’re going to make sure we have trials set up within the field.’ I think we ended up hitting 75 or 80 bushels per acre, which was almost double what their average was. Now, granted, Mother Nature cooperated and rained when it needed to rain. But the point was we were able to say fungicide meant ‘this.’ A different variety meant ‘this.’ Using lime, dry fertilizer on this part of the field meant ‘this.’ And we literally laddered it up to that number. To me, we can spend a lot of money on inputs and resources, but doing that, and actually just calling it the ‘kitchen sink’ but having our checks in place, fundamentally changed how that farmer grew soybeans moving forward. And we were able to increase the average over a lot of acres, 15 bushels. But if we didn’t identify what the core issue was and start to think about how we strategically implement different tests, we would have never gotten there. And I laugh because the same thing exists in product development, where you’re trying to build things for farmers. It’s like: ‘What’s the problem we’re trying to solve? How do we prove value, and how do we incrementally get there?’ So, whether it’s agronomy or software development or building the next widget for a John Deere tractor, it’s all the same when you break it down. It’s how you solve problems and measure it to make improvements.

RENEE HANSEN: Well, that’s a great success story, and the fact that, just in one year, how much they can learn and then take it to the rest of their operation over the next 3-5-10 years. And the profit that you’re getting out of that service is tremendous. I mean, it’s definitely worth the cost of the service.

T.J. MASKER: Absolutely.

RENEE HANSEN: You mentioned a little bit about where precision ag is going in the future, but where do you think precision ag is in the software space? So, we talked a little bit about automation with tractors and combines, but what about in the software space? Where do you think precision ag is going?

T.J. MASKER: I think it’s going to continue to get ‘smarter,’ which is kind of an annoying tagline, but it’s going to get smarter about how much you’re applying what rate on what date. A lot of this, we’re getting so good at understanding the impact, and we have enough data to understand it. I also think I’m pretty confident — we saw it in a past experience. I see it in the current one. The value of the mobile device and whatever you have with you is going to continue to dominate this space from a software perspective. You think about: ‘I can pull up Climate or the Ops Center on my phone and have an answer really quickly. I want to show my landlord how the field yielded in a second.’ Farmers are going to continue, in my opinion, to demand that the tools they’re using be accessible from anywhere. And so, precision ag, yes, there’s the technology in the cab. Yes, that’s important. But I would argue that this device — the phone, the tablet — probably more so the phone than anything is going to continue to be such a critical piece. It’s how farmers run their business, and they expect to have things on their phone. So, I would think if I’m working with a provider, that is going to be one of my number-one needs, and it’s also going to drive a lot of engagement for that farm, as well, which is critical for any tool you’re trying to use because a farmer’s going to get value out of a lot of things. But having that answer really handy with them whenever they need it is very, very valuable.

RENEE HANSEN: Yeah, getting your data any time, anywhere, I think, is kind of a little tagline that we use, even with one of our mobile apps that we have within Premier Crop. But I think I agree with you that farmers want it. They want to pull it up, and they want to see it. They need to show it, whether that be the banker or the landlord themselves. So, they’re looking at the field, getting ready to plant, getting ready to harvest. All of the above.

T.J. MASKER: Yeah, and it has to be easy to use, which is such a challenge, right? Because if you talk to the 50 farmers that I’ve talked to, you’re trying to pull out the nuggets that are similar between all of them, but there are always unique use cases. But I think as long as you’re solving for the 90%, you’re going to be well on your way to help the farm make better decisions, which is ultimately everything that we’re about and trying to do.

RENEE HANSEN: Great. Well, thanks, T.J. Thanks so much for joining us today. Really enjoyed all of your knowledge and your experience and sharing on the Premier Podcast.

T.J. MASKER: Awesome. Thank you.

RENEE HANSEN: Thanks for listening to the Premier Podcast, where everything agronomic is economic. Please subscribe, rate and review this podcast so we can continue to provide the best precision ag and analytic results for you. And to learn more about Premier Crop, visit our blog at premiercrop.com/blog.

Learn more about farm profitability.