As you are gearing up for harvest, there is a nervous excitement. You are about to get your final grade for 2019. How did you do? Did you make money? Did your decisions for the year pay off? These questions may give you pause, how do you measure such a thing? Is it the check that comes in the mail from the elevator? Is it the number that comes across the combine monitor? Is it, if your harvest map is green instead of red?

We help you answer these questions to establish your goals and create strategies to achieve them. Because we know it’s not about the highest yield, it’s really about how you profit. We can show you how profitable you were with our new Yield Efficiency Score metric.

Premier Crop has found a solution to combine all agronomic inputs, operations, yield and cost to determine your Yield Efficiency Score. A Yield Efficiency Score, similar to a credit FICO score, is a single number derived from multiple factors. The purpose of the Yield Efficiency Score is to take all your collected data within each field and use it to determine your per acre return to land and management.

Premier Crop helps you get started with a Yield Efficiency Score. At a minimum, we need yield files, field information (pesticide programs, planting rates, varieties, fertility programs, and input costs) that can be entered or gained from as-applied files from the planter or applicator, and your input costs. You don’t need the most updated equipment to gain efficiency knowledge, you just have to be willing to sit down with your advisor and walk them through your farm plan during the season.

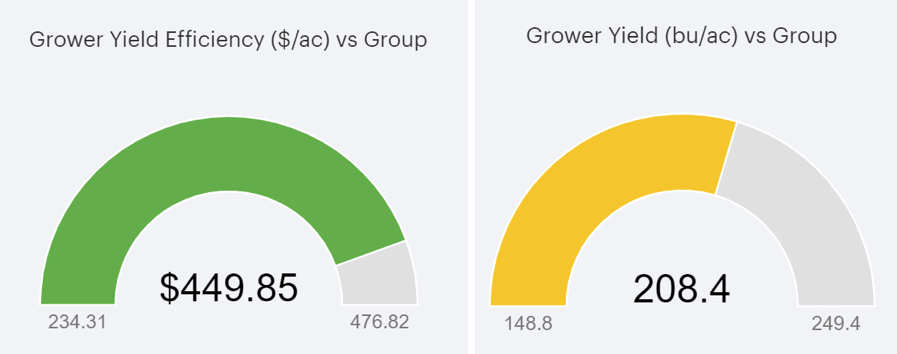

Once a Yield Efficiency Score is calculated you can visually see a benchmarking gauge that allows you to see beyond your own operation.

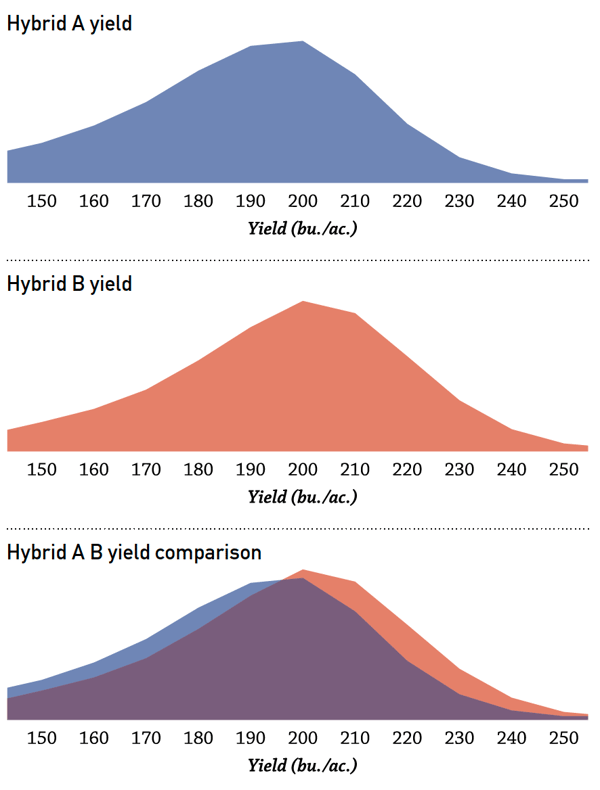

The Yield Efficiency Scores below are a true sentiment that obtaining the highest yield is not always the highest profit. Notice the image on the right shows that this grower has approx. -41 bu/ac less than the highest yield in the benchmark peer group, yet the image on the left indicates he is nearly the highest profiting.

The same can be done with seed, fertilizer & pesticide products/rates/times, field management, and economics.

As you track your data, year after year we can track how your efficiency gets better over time and how the decisions you make affect your bottom dollar. The longer you are in the program, the more confident your decision making will become. We strive for continuous improvement through shared learning and increased knowledge working along side you.

Yield efficiency is the metric you may not know you are missing, but yield efficiency has the ability to transform the way you view your operation and each individual field. At Premier Crop we know you have different needs and our goal is to help you reach them. If you are interested in getting your Yield Efficiency Score, contact Premier Crop now and an Agronomic Information Advisor will be in touch with you.

Your success is our success, we strive to give your data purpose.

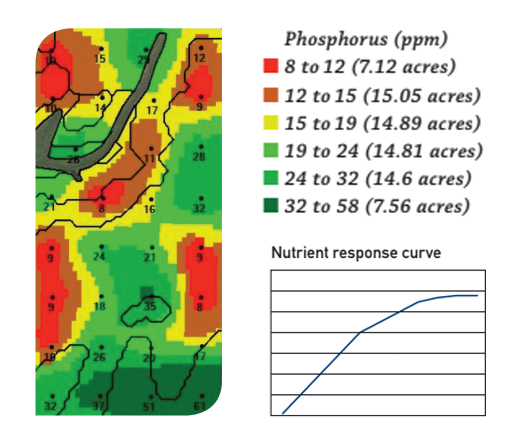

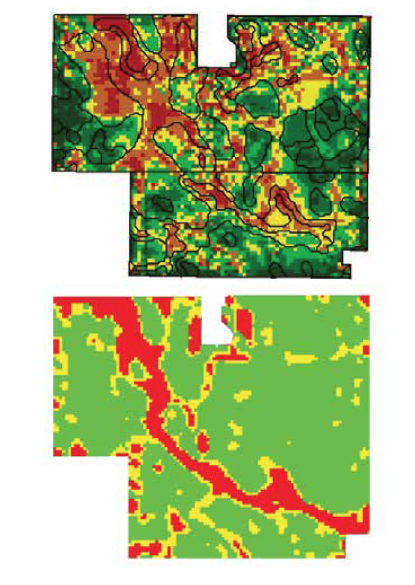

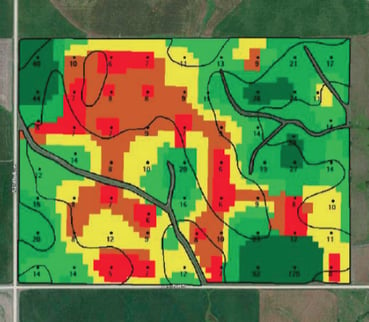

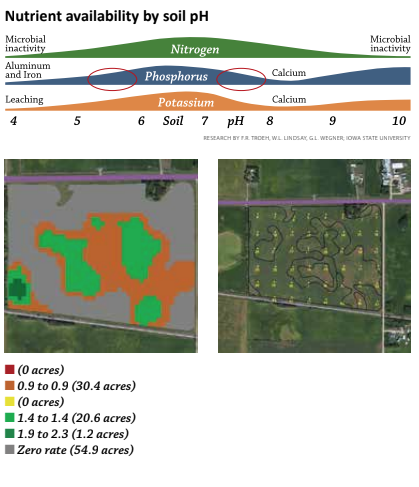

But there are at least three other reasons variable rate lime applications make sense. In many parts of the country, fields also have high pH areas. Applying a flat rate of two tons of lime on a field that has any high pH soils, makes a bad agronomic situation worse as phosphorus availability is just as adversely affected on high pH’s as it is with low pH’s.

But there are at least three other reasons variable rate lime applications make sense. In many parts of the country, fields also have high pH areas. Applying a flat rate of two tons of lime on a field that has any high pH soils, makes a bad agronomic situation worse as phosphorus availability is just as adversely affected on high pH’s as it is with low pH’s.