I have never liked the warning “you don’t get a second chance to make a first impression.” It always seems to futile and irreversible. But one example that I encounter frequently relates to how variable rate applications were first positioned by the ag input industry. Years ago, when GPS was first allowing us to measure differences within fields and variable rate controller technology was being pioneered, the value proposition presented to most growers was “this will save you money.”

With the exception of variable rate applications of lime, that first value proposition seldom proved to be true. And because the “save you money” value wan’t obvious to growers, some growers gave up and reverted to straight rate applications of all inputs. At Premier Crop, we seldom talk about saving growers’ money on inputs. We realize that what we might save on one part of a field, we’ll likely spend on another part. It’s not about saving money. It’s about maximizing profit; being more efficient in how we invest all input dollars.

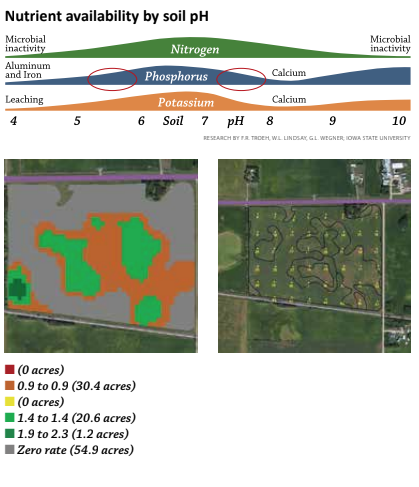

But that exception – variable rate application of lime – can be extremely significant in many areas and it’s worth exploring why it frequently saves so much. At some point in our farming history, most of us have seen this chart illustrating the relationship between soil pH and nutrient availability. Phosphorus (P) is a primary nutrient and a significant annual investment for most growers. Focus specifically on how phosphorus availability is influenced by pH. When I talk about why growers should know and pay attention to pH, I start with “P” availability. Correcting low pH’s helps unlock soil “P” reserves for the growing crop.

But there are at least three other reasons variable rate lime applications make sense. In many parts of the country, fields also have high pH areas. Applying a flat rate of two tons of lime on a field that has any high pH soils, makes a bad agronomic situation worse as phosphorus availability is just as adversely affected on high pH’s as it is with low pH’s.

But there are at least three other reasons variable rate lime applications make sense. In many parts of the country, fields also have high pH areas. Applying a flat rate of two tons of lime on a field that has any high pH soils, makes a bad agronomic situation worse as phosphorus availability is just as adversely affected on high pH’s as it is with low pH’s.

Another reason that is seldom talked about is organic matter mineralization. The bacteria that are needed for mineralization cycle aren’t active in low pH’s. Correcting pH can keep the soil’s natural nitrogen engine working well.

The third reason is an old one made new again. As we start to embrace IPM practices – crop rotations, herbicide rotations, cultural practices, etc. – to deal with weed resistance, soil applied herbicides will be part of the solution. And some of the most effective products have pH interactions, including carryover to other crops in your rotation. How will your advisors make the best recommendation without a pH map of each of your field?

There are many reasons to variable rate apply lime, but you can’t consider them without an accurate geo-referenced soil sample. It’s a great way to get started and the savings in lime cost by only treating the low pH acres will more than pay for the cost of the soil sample!