I’m a big believer in the practice of split-applying nitrogen — specifically sidedress-applying a portion of the nitrogen after planting. Being able to apply part of the nitrogen closer to the plant uptake always made sense to me because the nitrogen is less available for loss before that time. However, oftentimes it is difficult to find an advantage to sidedressing in the data.

It can drive me crazy having access to millions of acres of data and not have the data confirm something I believe! Or worse yet, show the exact opposite! For example, there have been plenty of years when fall-applied nitrogen appeared to do as well, if not better, than spring- or split-applied.

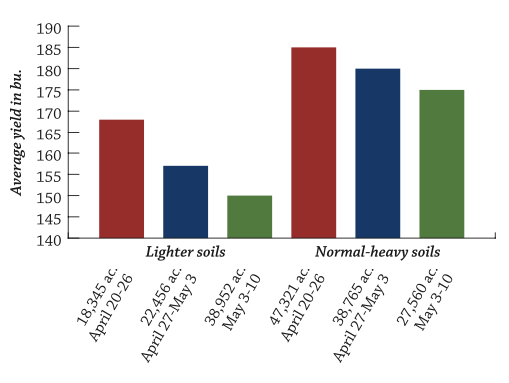

Here are some of the lessons I’ve learned over the years. First, there can be “sectional bias” in the data. For example, growers “select” their heavier soils for fall applications for agronomic reasons — ability to hold ammonium nitrogen. Likewise, they might choose their lighter soils for sidedressing. Simply comparing yield by nitrogen timing can lead to a wrong conclusion. Looking at nitrogen timing by soil type can be an obvious next step in correcting for selectional bias.

A second reason that sidedressing might not show up as being superior in data analysis is due to the fact that nitrogen applications might not be the yield-limiting factor! If applied nitrogen is not what’s yield-limiting, then timing of application won’t likely matter or show up in data analysis. In much of the high-organic-matter portion of the U.S. Corn Belt, university researchers estimate that 50% to 70% of the nitrogen that feeds the plant is soil-supplied and not fertilizer-supplied. It’s no wonder there are years when the relationship between applied nitrogen—regardless of timing — and yield is insignificant.

The last reason is the one I hate — it’s that I could just be wrong. When believing so strongly in a concept, it’s very difficult to consider that you have it wrong. But I’ve been there with sidedress nitrogen applications. From the data, the best explanation is that there are years when, in some areas, we don’t get enough rain after the sidedress nitrogen application to move that newly applied nitrogen into the root zone. In those drier years, the top of the soil profile is dried out and the plant is feeding deeper. You’ve all been to a field day where someone used a backhoe to do a “root dig” to illustrate this point. You may have walked away with a mental note that what is below ground is bigger than what is above.

What do you do when data analysis doesn’t support your own theory? For me, the first answer is to keep digging in the data. I’m still a believer in split-applying nitrogen — including sidedressing a portion — but living through those dry summers would lead me to get the work done early. My second answer is to focus on pounds of applied N per bushel. Can I produce the same or more with less applied nitrogen by altering timing?

Got Data?

- What are some of your theories or beliefs that are not showing up in your data? Can you dig any deeper?

- How might you weather-proof your nitrogen program? How might your data help in the process?

Originally published in Corn and Soybean Digest.