Today we are talking with Dan and Renee about the significance of using yield efficiency in your operation.

About Dan: Founder and current VP of Technical Services. Since founding PCS in 1999, Dan has witnessed many changes and transitions in the ag data industry.

If you are enjoying the show, tweet us using #PremierPodcast.

DAN FRIEBERG: When we talk about yield efficiency, to me, it comes down to us being willing to track the economics of the decisions that we’re influencing with the grower and tie it out economically for the grower. In a lot of people’s minds, yield has theoretically represented higher profits, but we also know that’s not necessarily the case. Sometimes higher yields come at so much higher costs that they aren’t more profitable. In general, that hasn’t been that wrong. If we can produce higher yields many times, it is more profitable because you’re spreading more units of production over the same fixed cost, and one of the big fixed costs is land cost. Whether you produce 100 bushel of something or 200 bushel of something, unless you have a flex lease, a lot of times your land cost doesn’t change. There are rental agreements where the land owner is sharing both in the upside and the downside associated with higher yields and all that. So, yield efficiency, for us, is the dollar-per-acre return to land and management, and the reason we define it that way is because we don’t influence what somebody pays for land. We don’t influence their land cost.

Don’t get me wrong. They can use data. They can use the analytics we provide to make land rent decisions, to make land purchase decisions. So, they always have. They use analytics to help them decide what to rent and what to buy and all that. On a yearly basis, we’re not impacting land cost, and management cost is another one where we probably don’t have as big an influence.

There’s a lot rolled into management. For a lot of operations, it includes family living and health insurance and a whole bunch of other things that are really a key part of the operation but not something that we advise on. But we do advise on nutrients. We spend a lot of time helping growers manage their nutrient investment. We help them a lot with the seed investment, both what they choose to buy and where they plant it and at what rates. And we also help on crop protection decisions.

Then, the fourth one is operations. We don’t advise on operations. We don’t get into what equipment they should buy. There are a lot of data analytics tied to operations. We can analyze no-till versus conventional till, and we can break down and analyze differences in cost associated with different tillage types. Yield efficiency, for us, is just about how do we drive higher return to land and management? We do that through how we advise growers, how we advise them to spend nutrients, seed and crop protection dollars.

RENEE HANSEN: So, why is that becoming so much more important now than it was 10 years ago?

DAN FRIEBERG: It has always been important.

RENEE HANSEN: But are margins getting tighter than they were 10 years ago?

DAN FRIEBERG: Not today. They just blew. Margins are record high. I mean, people’s optimism at the farm gate has bounced way back. We’ve had this dramatic uptick, so margins are stretching back out. So, opportunities for people to make money, but Renee, it doesn’t matter. In good times and bad, this message resonates. It makes sense no matter what. Spending your money wisely just makes sense. Are growers more aggressive when the commodity prices are high? Some of them are. Some of them are way more aggressive. Will more growers take a chance on fungicides because of high commodity prices? Absolutely. Commodity prices have increased more than fungicide prices. When commodity prices are high, it takes less bushels to pay for the fungicide. So, more growers will probably take a shot at fungicides this year than in past years.

RENEE HANSEN: We also talk about, sometimes, growers wanting to grow their operation. Tell me more about that.

DAN FRIEBERG: It’s really natural. It’s just the competitiveness of agriculture. There are a lot of growers who are adding to their operation. They’re wanting to add. It’s all about spreading yourself and your employees and your equipment over more acres. If you can add another thousand acres and still farm in a timely fashion, it makes it more economical. Combines are really expensive, so being able to spread that combine over another thousand acres drives your per-acre costs down, which is the same with your labor. There is additional labor cost to farm another thousand acres. But even labor — employees come with a benefit package. You have to pay benefits. There are a bunch of employee costs that, if you can spread it over another thousand acres, it helps pay the bills and helps you be more profitable.

RENEE HANSEN: So, can you explain the metric that we’re using? We’re using a gauge or a metric, or we’re giving a yield efficiency score. We’re using that per operation, and we’re also doing it per field because we can do it spatially. So, can you just tell me more about each of those?

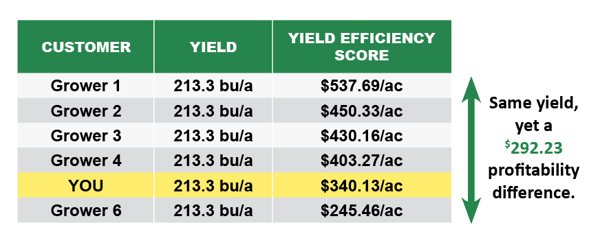

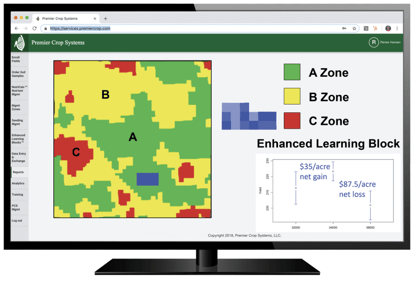

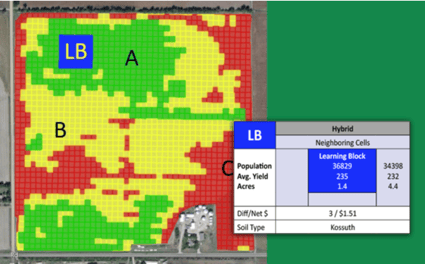

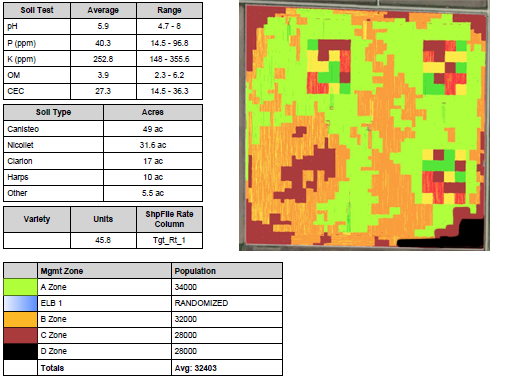

DAN FRIEBERG: Sure. So, the gauge you’re referring to is what we call the Yield Efficiency Score. Really, it’s a fairly simple formula. It’s just a benchmark selling price that every user gets to set. We’re not benchmarking who sold the best, so it’s a benchmark selling price times your yield. So, Premier Crop, part of our analytics program is we’re using the yield file. So, we’re receiving all this yield data. It’s benchmark selling price times yield minus your investment in nutrients, seed, crop protection products and field operation. What’s left is return to land and management. How many dollars per acre do you have left to pay for your land cost and your management costs? So, what you referred to is part of what we’re able to do. Let growers benchmark themselves, their yield efficiency score versus other growers in their area anonymously. Growers like that. It’s just another way to make sure you’re on track or just see how you’re doing compared to others.

So, that comparison, people like. They like to be able to anonymously compare with really quality data. That attention to getting the data right is really a big deal and having good quality data. So, that’s a big piece of it, but then the other part you referred to is being able to take it down to a field level. It’s not just benchmarking outside your operation. How do you compare to others? It’s within your operation. If you’re farming 50 fields, just being able to rank order those 50 fields from a yield efficiency standpoint, return to land and management, that’s a significant piece of analysis.

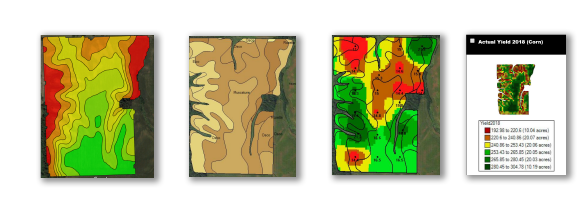

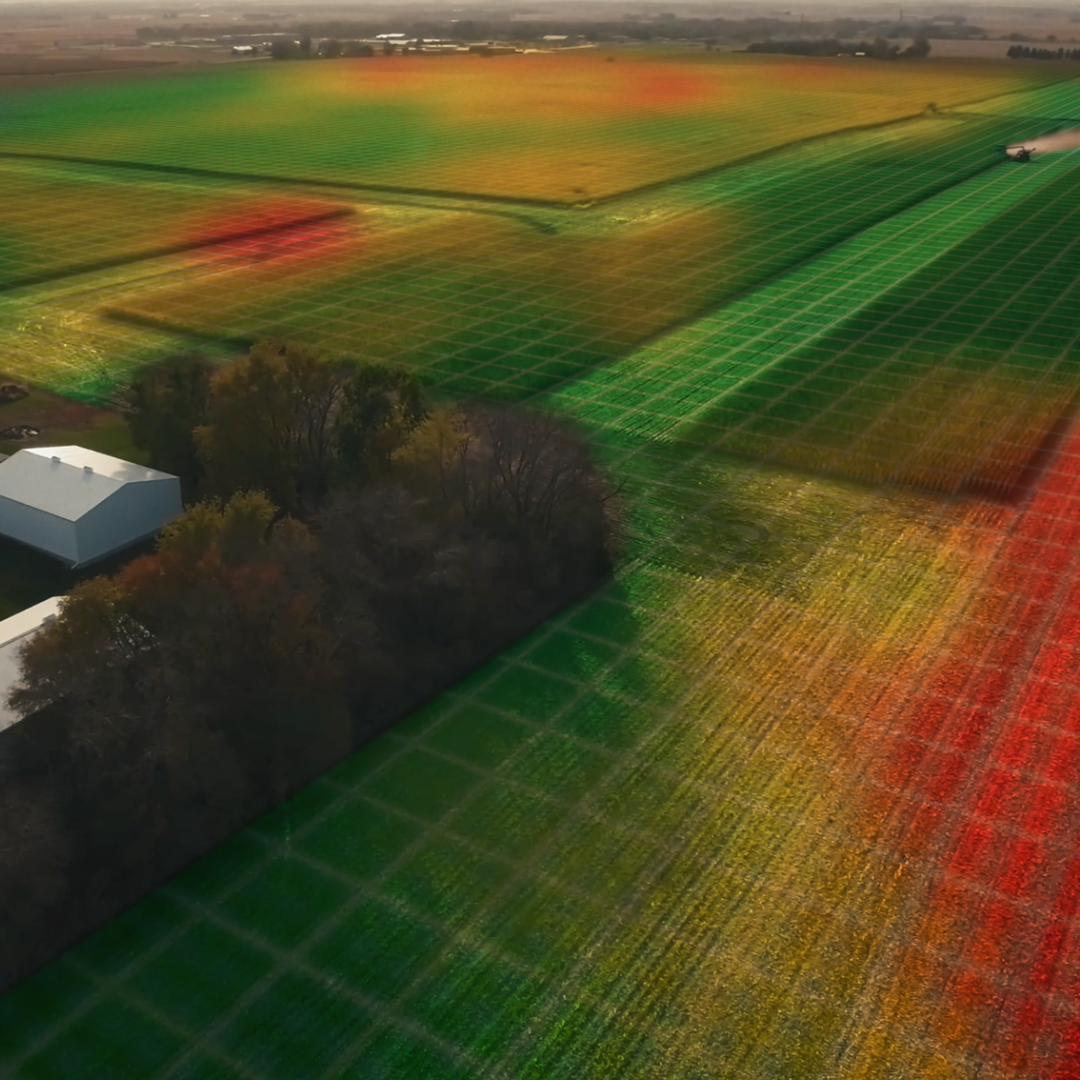

Renee, as soon as growers see those scores, trust me, they do the math so fast on land costs. They know exactly what their land cost is for each field. It’s not something they have to go look for. Then, the last one that you talked about is being able to do it spatially within a field, which means we can do it by management zone within a field. Which is really, by far, the most important to me because what we consistently do for our customers is we spend more in certain parts of the field. We know there are a lot of times, if you’re following our recommendations, it could be a $50-or-$80-an-acre higher input spend. In some parts of the field, we’re spending significantly more on nutrients, and we’re increasing the seed population.

So, we could easily spend more in part of the field, and the reason it’s so important to be able to track yield efficiency spatially within the field is so that, at the end of the year, we can prove to the grower that extra $50 an acre in the best part of the field generated more, far more, than the $50 of additional input costs. For me, this is, just this yield efficiency thing, is what we should have done. 10 years ago, yeah, we probably should have pushed harder to do it then because I think growers always respond to anything if you can prove that something pays for a grower. They’ll respond to that.

For a lot of new growers — we’re really blessed with a lot of growers who have been with us for decades, and the reason they have is we’ve convinced them over the years that it pays. They wouldn’t keep buying our service if they weren’t sure it was paying. But for a lot of new growers, this ability to tie economics and just have a report card every year that shows: where we spent more, we made more, or where we spent less, we made more.

Throughout the entire field, being able to document that what we spent made them more in either higher input investment or lower input investment. Really, growers respond to profitability, but there are so many people who talk about it, and they have no way to prove it. Everybody that drives up the driveway talks that way, but they can’t prove it. They can’t. That’s kind of the magic of what we do. This is the grower’s data. We’re using all the grower’s data, and we’re proving it.

RENEE HANSEN: Yeah, so tell me about using all the grower’s data. You say others are saying that they use profitability. So, what are we doing to prove it? You kind of gave a list of the seed, the nutrients, operations, crop protection, but can you go dive a little deeper?

DAN FRIEBERG: Sure. So, when we talk about all the grower’s data, it starts with just naming the field and getting a field boundary. Once you get the field boundary, you can go get the soil’s data, and now you can get LIDAR data, which is elevation data. So, you can kind of have an idea of how water moves within the field, but then we just keep adding to it. Soil sample information is a big part of it, whether it’s zone or grid sample. A lot of our customers are grid samples, which means we’re measuring organic matter and pH and soil test nutrient levels within the field in small increments, like couple-acre blocks.

So, we’re measuring all those layers of data, and then, when the planter makes a pass across the field, we’re grabbing planting date. We have row spacing and population and the hybrid and variety that got planted. And that hybrid and variety is not just the company and the number, but it’s also the trait package. We’re able to sort SmartStax versus VT PRO versus some other traits. When it comes to nutrients, we’re grabbing the soil sample data. For us, it’s about what we add, whether we’re making the addition of nutrients through manure, or whether it’s with commercial fertilizer. We’re tracking the rate, cost, timing, and if it’s fall versus spring versus side dress. We can track all those details. If the nutrient had an additive, we’re tracking that, and then you step into crop protection.

Now, because of weed resistance, crop protection is, again, becoming much more complicated than it was for a decade when it was just how many ounces of Roundup people were using. Now, it’s a lot more. There are a lot more products being used. It could be 40 different combinations of additives and crop protection products. Each time, it’s the product, the rate, the source, timing, costs, so just terrific detail. Tillage, field operations, how many passes, what the passes were. Just try to incorporate as much detail as we can about what’s happening within the field so that we can do the best possible job of managing all those inputs.

RENEE HANSEN: So, how do we compare this anonymously with another grower, apples to apples? Because you just listed a ton of data layers, a ton of cost information, and let’s say somebody else doesn’t have all that information in the system. How can you compare that apples to apples and get a benchmarking yield efficiency score?

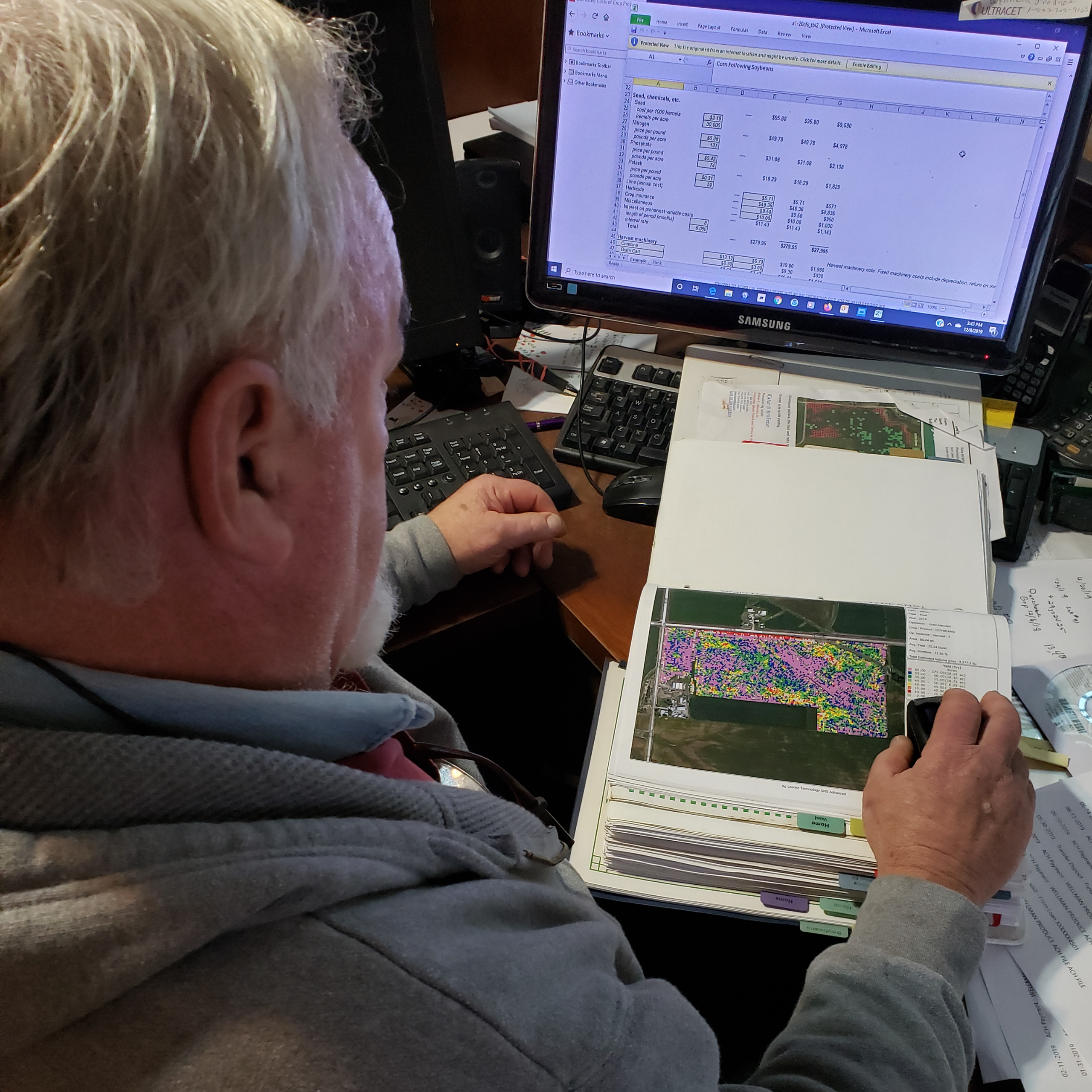

DAN FRIEBERG: We can walk people through this really quick. Renee, there are a lot of growers who have data. They just don’t — it’s scattered. I mean, they have data in the Ops Center. They have it in Climate. They have it in some retailer’s software. I mean, it could be a retailer’s software. It could be on their own. I mean, it’s all over the place. Sometimes it’s not in a digital format. Sometimes it’s written down. It’s just all over the place.

But a lot of growers have data, and part of it is how we pass down farm equipment. Every time somebody buys a new piece of equipment, they trade. So, it’s like existing farming operations. They trade, and as they trade, somebody else trades. And when they trade, they trade the technology with it. They’re not stripping the monitors out of the cab each time they trade. A lot of times, they’re not. So, that technology is being passed down, meaning there are a whole bunch of growers who don’t operate new farm equipment, and they have the technology in the cab. There are just a lot of growers who have the capability. They have the capability of collecting data and capturing data, and they have a lot of variable-rate capability of which a lot of them aren’t using.

RENEE HANSEN: Yeah, I was just going to ask you that too. Can you elaborate? The growers have so much that they can do with their data. Do you feel that they don’t even know what they’re capable of getting and gaining with the technology they already have?

DAN FRIEBERG: I think, a lot of times, with a lot of people — a lot of growers and a lot of people — it’s finding somebody you trust. If the person you trust for advice doesn’t talk to you about this or doesn’t have a solution, you might not ever pursue it. You might not pursue it on your own because, in your circle, nobody’s championing why you should be using the technology in the cab or your data to make better decisions.

RENEE HANSEN: Well, if somebody doesn’t mention it to you, you don’t know what you don’t know.

DAN FRIEBERG: Yeah, you don’t. You literally don’t. So, I think that’s part of what happens. Another place I wanted to go, Renee, was people talk — I mean, when I talk about everybody that drives down the farmer’s driveway has a profitability message, a lot of times, they say return on investment. They wrap everything. So, the number of times people say ROI or return, it becomes a buzzword that nobody backs up. Nobody has. When they talk about backing up their ROI, they pull out some plot book. It’s some trial that happened someplace else.

You can’t really tell somebody the ROI unless you do an experiment in the field, and that’s really what we do all the time. We do experiment after experiment, in volumes, in growers fields. It’s all in pursuit of having better recommendations so we can calculate ROI. It’s so that we do know whether that input paid or not. If I go out to a grower and I talk to them about nitrogen rate, and their total N rate is 200 pounds of actual N, and I think that they’re over-applying, the best possible way for me to have that discussion is just to suggest that we put a lower-rate experiment in their field. It doesn’t have to be a lot of acres, but if that works, then the grower saves money and gets higher yields or same yield. That’s a starting place and a discussion.

Same with everything. Every input decision can become an experiment. So, to me, the best way to get an ROI is to simply do a trial. And we’re not talking about — when I got in the business, a trial meant flags. It meant field flags, and it meant a ‘weigh wagon.’ That’s how you did trials. You just spent all your — like I spent all fall running around with a ‘weigh wagon.’ Literally, just day and night, running around with a ‘weigh wagon’ because that’s the only way you could do a field trial. And now, everybody’s got the ability to measure. The monitor in the cab is measuring.

So, a little bit of help on calibration, making sure you’re calibrated, and you’re off and running. We can use the technology to execute field trials, and it’s just so much easier than it was years ago. And it really just opens the door. It opens the door to back up the ROI message over and over again. It doesn’t have to be results from somewhere else. We say growers love local data, and you can’t get more local than my fields. That’s who we are. It’s not: ‘How did it do somewhere? How did it do for your neighbor?’ It’s: ‘How did it do for you?’ And doing trials is a big piece of what we do.

RENEE HANSEN: Yeah, and you’re talking about the buzzword of ROI, and I feel like Premier Crop has coined the buzzword of yield efficiency. I’m starting to see yield deficiency pop up in other places, people talking more and more about yield efficiency rather than using ROI. And why is yield efficiency a more important message than ROI?

DAN FRIEBERG: So, for me, they can be really similar. I mean, they can be part of the same discussion. So, for me, yield efficiency is just combining economics and agronomics, and it’s at every level. It’s sub-field, in a trial and management zones in a field. It’s this field compared to another field. Across your whole operation, how do my fields compare?

Then, it’s being able to go beyond your own operation to: ‘How do I compare to peers in my neighborhood or my region?’ A lot of times, when I think of ROI, I tend to think of it as — so, yield efficiency is this all encompassing bucket of nutrients and seed and crop protection and field operations. But, for me, ROI is more about individual components that make up those buckets.

If I’m a grower, it’s like: ‘What’s my ROI if I put 50 pounds of Y-DROP nitrogen on?’ So, later nitrogen. What’s my ROI if I do a fungicide? What’s my ROI if I do a biological? All those things, all those decisions roll up into yield efficiency because they’re all input costs. And, hopefully, they impact yield. So, all those things roll up into yield efficiency. But when I think of ROI, I’m thinking of individual decisions. I mean, decisions I’m making about input components of what goes into yield efficiency.

RENEE HANSEN: Well, and I think it’s important to note, also, it doesn’t have to be with a variable-rate application of anything. You can still get a yield efficiency score with flat rate.

DAN FRIEBERG: Sure. As we onboard new growers, that’s a big deal, just to capture where they are. Before you started doing anything, what was your yield efficiency?

RENEE HANSEN: Yeah, so if somebody is coming on board and is not doing any variable-rate nutrients or seed, they can still get a yield efficiency score in a benchmarking setting.

DAN FRIEBERG: Yep. Renee, earlier on, I just remembered what it was I wanted to talk about. Earlier on, you kind of said or you asked something like: ‘Why don’t more growers, or why do I think more growers don’t do this or think like this?’ I think that a lot of growers have the attitude of: ‘Been there, done that. Got the T-shirt.’ They think they tried it. Somebody pitched them an idea, and told them about precision ag or whatever buzzword they used at the time. Then they created this expectation and didn’t deliver.

RENEE HANSEN: There’s no follow through.

DAN FRIEBERG: Yeah, so there are a lot of growers who, you meet with them, and they say: ‘Tried that 15 years ago. Didn’t work here. Doesn’t work here. Maybe it works where you’re at. It doesn’t work here.’ Then, you really start asking questions about: ‘What do you mean it didn’t work?’ And what you find out is they never compared. They never looked at the relationship of yield and the prescription, whatever it was. Nobody did the basic analytics for them.

The classic one, 20 years ago, was people would say: ‘I’m going to grid-sample your field. We’re going to variable-rate apply nutrients. And all these multi-colors, from high to low, on the map, we’re going to even all those out. We’re going to build up the low areas pull down the high areas. Your map will all be green. We’re going to make your field uniform.’ And 12 years later, the field is no more uniform than it was to start with. And my point is that should never have been the goal. You get paid on yield efficiency and on generating more return for every dollar you invest. You don’t get paid for making your fields uniform.

The reason it didn’t work, Renee, is because the high-yielding areas tend to pull down nutrients because you’re consistently removing more nutrients from those areas. And even though the equation, the variable-rate equation, was supposed to be dealing with that, it never caught up. Those high-yield areas just kept producing more and more, removing more and more, and the reason the field wasn’t more uniform at the end of four years or 12 years was just they never kept up with that additional crop removal associated with really high yields.

RENEE HANSEN: So, the way I see it, utilizing a yield efficiency score, the way that we are calculating it, can potentially help a grower to grow their operation in a multitude of ways. Not only by gaining more acres, but they can also, potentially, gain more profits with what they already have by optimizing and utilizing some variable rate to see where their yield efficiency score is. They should be able to see what fields really aren’t producing as high, so they shouldn’t be spending as much in that field, in certain parts of the field.

DAN FRIEBERG: I think the whole yield efficiency message is just, I think, it helps growers know their costs. It helps them know. I mean, it’s just putting data to work for you. Really, like you say, you can drill down on which fields are most profitable, which aren’t. You can drill down on which parts of fields are most profitable. I think the more you help growers know their costs, the better managers they are.

RENEE HANSEN: But I feel like they already know their costs. I feel like most of them are like: ‘Oh, no, I got that. I got it on a spreadsheet, have my tally and know exactly what I’m going to be spending on my inputs.’

DAN FRIEBERG: And you’re right. They know their costs across the whole operation, probably. I think the difference is just knowing it within field by field and within fields. So, it’s probably just the nature of being able to break it down into finer resolution. Renee, what we don’t do is take university-average cost associated with farming and divide it by their yield. This is not pretend economics. This is tracking. Like I say, we track if that part of the field is getting 10,000 more seeds than the other part. We’re tracking the cost associated with that 10,000 more seeds in the best part of the field.

RENEE HANSEN: We talk about plans, like having a plan and then pushing that to ‘actual.’ This is the ‘actual.’ I mean, we’re talking about what actually happened.

DAN FRIEBERG: Growing your operation is a tough one, Renee, because there are so many pieces to it.

RENEE HANSEN: Right.

DAN FRIEBERG: One thing that stands out to me is — it was from a winter grower meeting. And these growers were talking about how there was an area where there’s a lot of livestock also, and they were talking about how every pen of pigs or cattle that they sold, they knew the economics associated with that pen, meaning they tied it out economically. In livestock, it’s just such a part of the culture. Every unit of production gets tied out economically.

So, sometimes, I’m so jealous of the livestock industry because I feel like: ‘Okay, you guys are way ahead, like we’re playing catch up.’ But that’s really what we’re trying to do. Tie out every unit of production economically. It’s not enough to know just what the total weight was. It’s converting the weight and the input cost into dollar returns. And that’s kind of what we’re focusing on.

RENEE HANSEN: Thanks for listening to the Premier Podcast, where everything agronomic is economic. Please subscribe, rate and review this podcast so we can continue to provide the best precision ag and analytic results for you. And to learn more about Premier Crop, visit our blog at premiercrop.com.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

- For more helpful tips and insight on all things data and agriculture, visit our blog at http://info.premiercrop.com/blog

- Curious about precision ag? Download our 5 Steps to Getting Started Guide: http://info.premiercrop.com/5-steps-guide

- Ready to cut through the bull? Download our No Bull Guide to Precision Ag: http://info.premiercrop.com/field-profitability-guide

- Podcast provided by Premier Crop Systems. Learn more about us at https://www.premiercrop.com

Image from

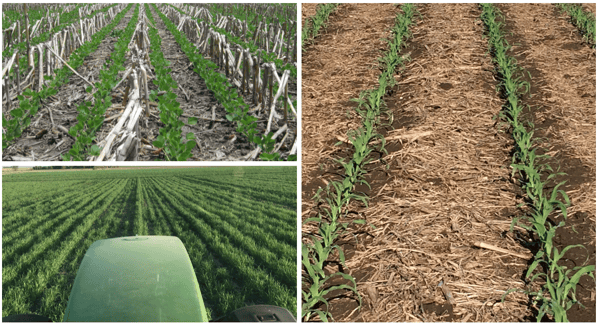

Image from  Upper Left: No-till; Lower Left: Cover Crop; Right: Row spacing

Upper Left: No-till; Lower Left: Cover Crop; Right: Row spacing