We often use the phrase, “Everything agronomic is economic.” What does that really mean?

First, let’s first define agronomics and economics. What is agronomics? That’s everything that we do in the field related to making good management decisions. It’s deciding how much fertilizer to apply and where to put it, planting rates, crop protection, tillage systems and how to incorporate all of this into the farm. Those all go into how we grow our crop. On the economics side, we’re talking about all of the money involved in farming. Farming is a business, and just like any other business, you need to make sure you have cash flow so you have the opportunity to farm again next year, and the year after that. So, how do we focus on agronomics and economics? We do that by analyzing growers’ data. We use that knowledge to help them make decisions on their farm.

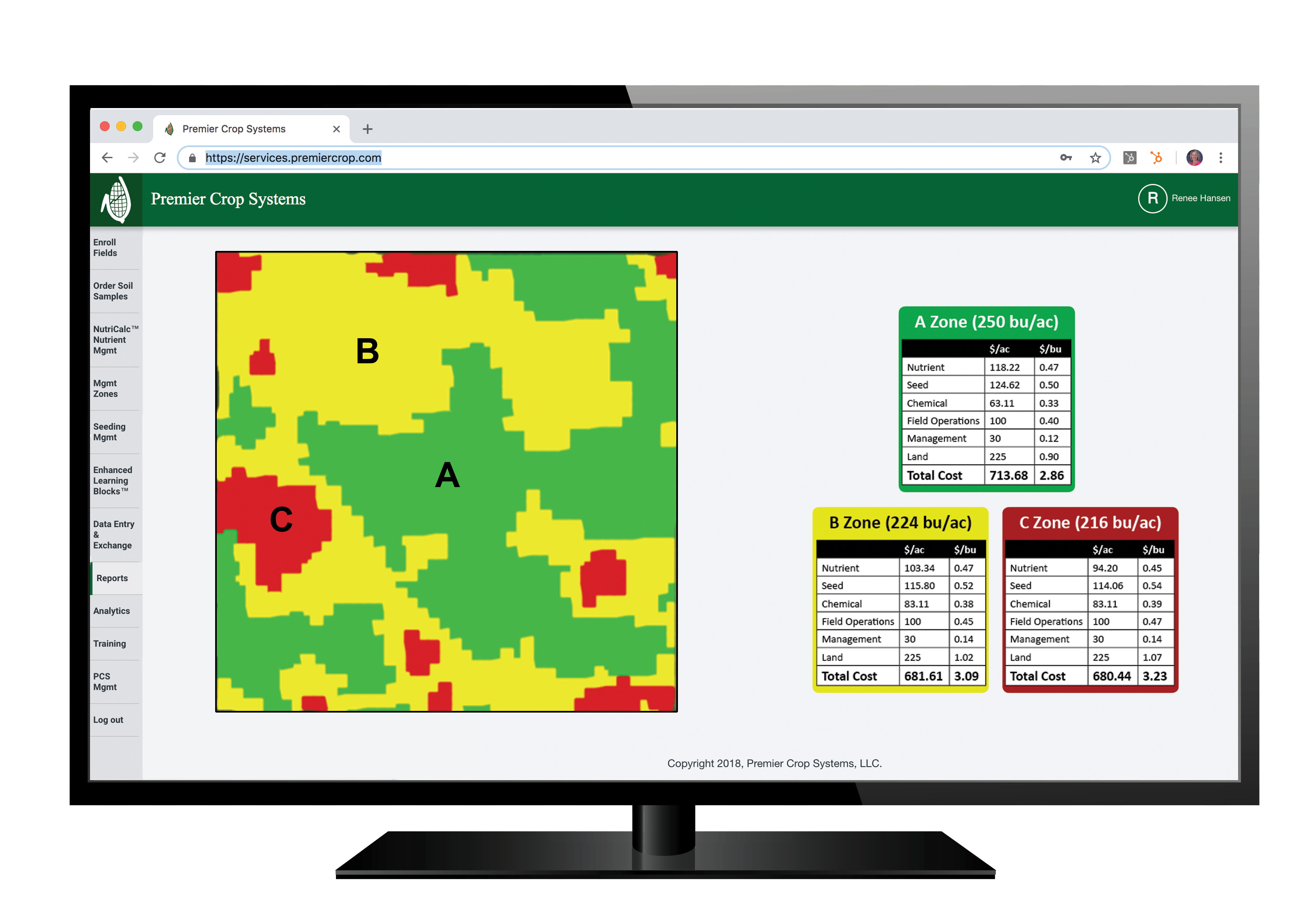

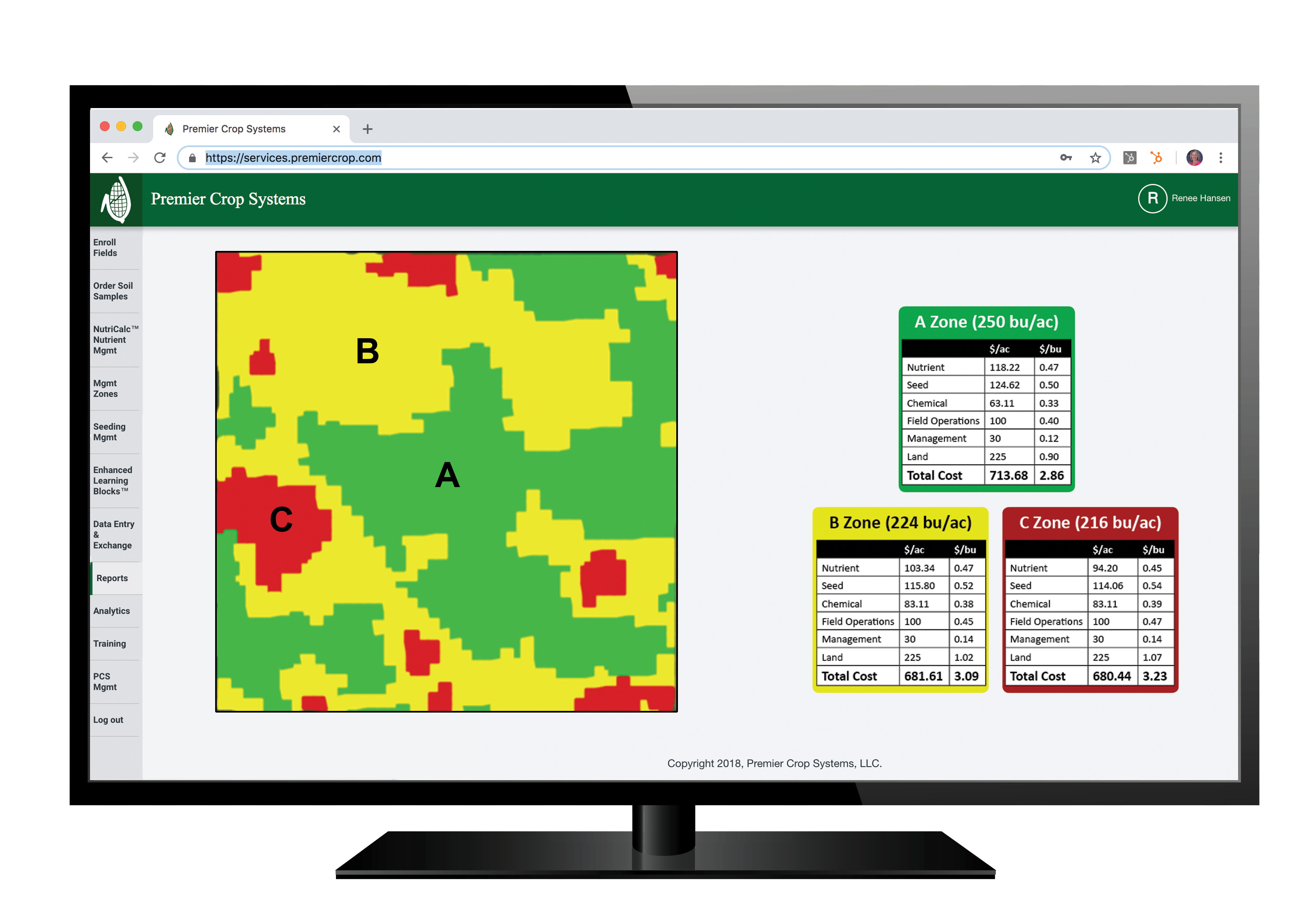

Knowing what you’ve done on the farm in the last five, 10, or 20 years can provide valuable knowledge as you plan into the future. However, if you never take that data and don’t use it to make decisions, it’s not doing you any good. It’s important to invest time into collecting your farm data. We work with growers to analyze their collected field data. We add costs to the layers of data including product cost, operations cost, management cost if they have any land-specific cost, and tie that to the yield file so we can see what is making agronomic and economic sense on the farm.

It’s fairly easy to tell where there are higher yields, but it’s a lot harder to know if that yield increase also caused an increase in the pocket book. Did the decision pay for itself? Did you produce enough bushels to offset the cost of production? Every pass across the field matters agronomically, but it also has a cost associated with it. We give you three steps to help combine your farm agronomics and economics below.

1. PLANTING

When you’re preparing to plant, your seed has the highest yield potential it’s ever going to have. Everything we do at Premier Crop is aligned with protecting yield potential, and planting population is a big aspect of this. If you overcrowd the plants, you’re going to make them compete for resources, which will end up reducing your yields. On the flip side, if you have too low of a population, then you’re reducing your yield potential by not having enough in the first place. You can’t produce more bushels of corn if you never plant the seed to begin with.

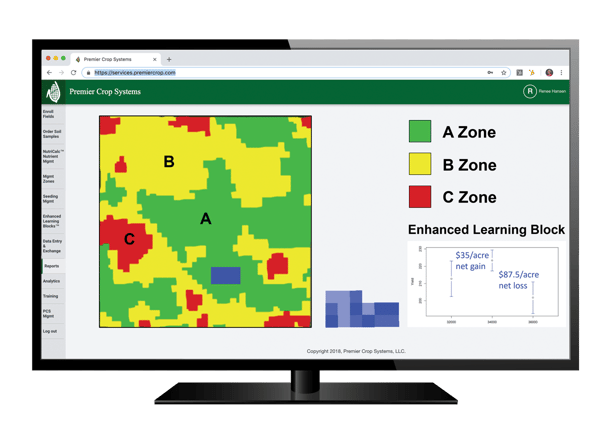

Combining agronomics and economics is about finding the right rate for the right part of the field, which we accomplish with management zones. A management zone is not just a seeding rate like it is with many other precision ag companies. We manage the field and the operation off of the zones. We break fields into high-producing areas, which are A zones, average-producing areas, which are B zones, and lower-producing areas, which are C zones. The B zones are the types of areas that do pretty well year in and year out, but they don’t have the capability to be the highest producing areas of the field. Our C zones could look like a wet spot, an area shaded by trees, or a family of deer could live nearby and eat it all the time. We manage nearly everything based on these zones.

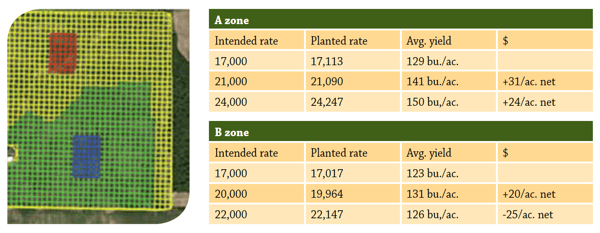

In the A zones, our high-producing areas, we push planting populations. We plant more seeds in these areas because these parts of the fields have the capability to produce more bushels. In the C zones, we’re going to pull back our population because we know those spots just simply don’t have the yield potential. By labeling it as a C zone and understanding that it is not going to produce as well, we can manage risk by lowering the planting population. This practice will save money on seed costs in this part of the field because by lowering the population, we have reduced seed cost, which helps the bottom line. However, if we can get part of the field from a C zone to a B zone, or from a B zone to an A zone with fertilizer or any management practice, we will go after that to increase our return to land and management, what we call yield efficiency.

2. FERTILIZER

When variable-rate technologies first came out, the discussion was: “It’s going to save you money and reduce your fertilizer usage.” We found that’s not always the case, though. Instead, grower’s are making better decisions with their planting or fertilizer dollars. They are putting those dollars in the areas of the field where it’s needed and where they can get a return on their investment. We are driving farming towards thinking more on the economic side of the business.

In general with farming, if you’re doing a straight rate across the field, you’re essentially treating every acre the same. We know that every acre is not the same because when you’re harvesting, even if you don’t use a yield monitor, you can see variation in the amount of loads you’re taking off. You can tell how good or bad the corn is as you’re driving across the field. So, why would you treat your inputs the same if you’re not taking the same amount off of it at the end of the day? That’s why it’s so important to tie the economics to planting, and fertilizer. That is where the real benefit lies.

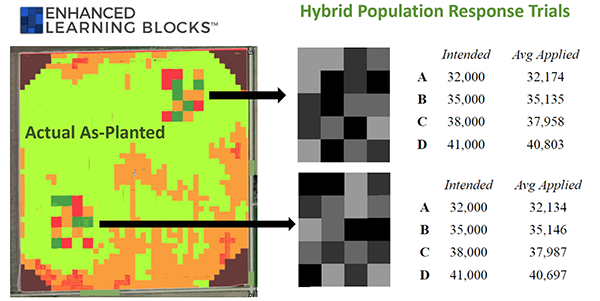

Even if you are locked in on your planting populations, placing different checks in a field through different years allows you to gather historical data and be able to check and say: “In this year, if we’re looking at a cold, wet spring, this is the best population to go with.” Even if we don’t use that specific data in the next year, we are still collecting it for future years.

It is also important to factor in your planting population when you’re determining your nitrogen rates. We often use the example: If you invite more plants to dinner, you have to have enough food to feed them. We could apply a straight rate, but we’re going to be overfeeding the poor-production areas and underfeeding the high-production areas. So, if you have a higher population in the A zones, you need to account for the added food they’re going to need. We can also push the nitrogen rates a little higher in the A zones because we have the capability to produce more bushels, not just because of the higher population but just because the ground is better. By pushing that, you’re taking a little bit more risk, but it’s a smart risk.

3. ANALYTICS

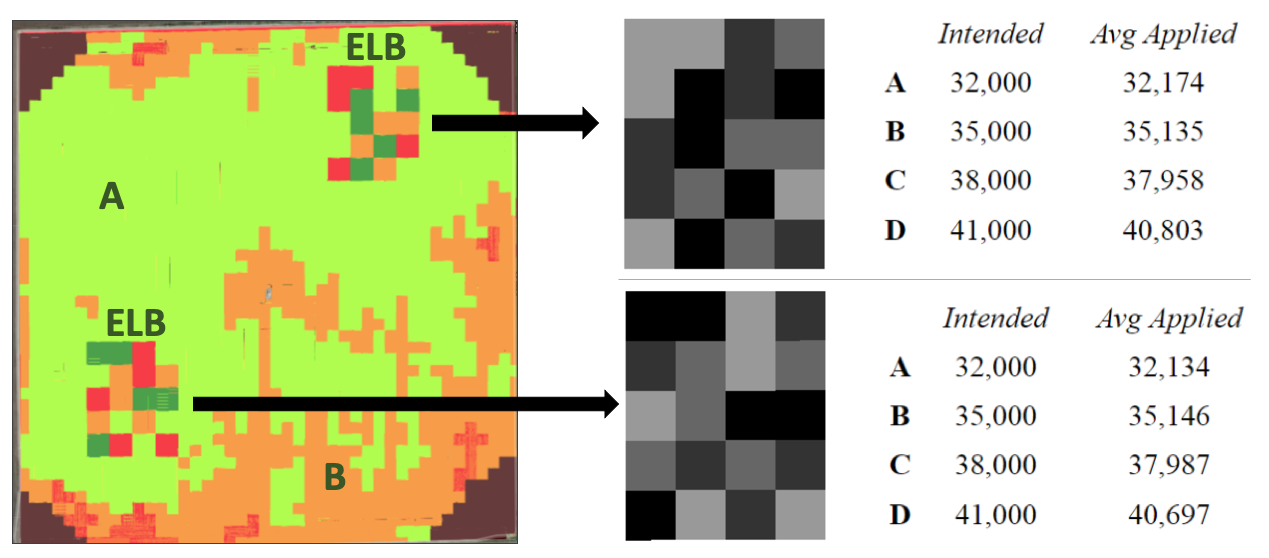

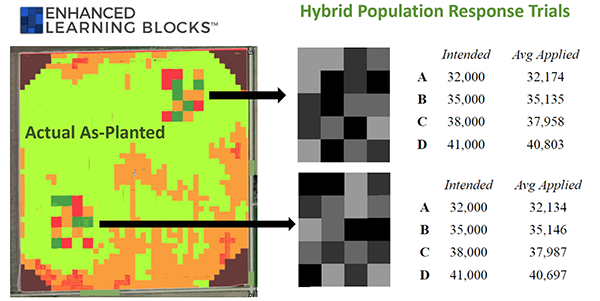

To get started looking at a grower’s analytics, we first pull yield monitor data. Then we look at everything the grower has done throughout the year, whether it’s fertilizer, lime, planting, nutrients, or crop protection products. We dig in and see what the economic benefit was. When planting, did we build small test plots into the planting maps for our growers called Learning Blocks. We then use the information from our all of our data within a management zone to see if we have the right rate. Learning Blocks not only show us what produces the highest yield, but it also shows which population provides the greatest return on investment. Once the prescription is in a grower’s monitor, they can just focus on farming. It’s very little thinking on a grower’s part because we’re constantly constantly checking our work. It is important that we prove what we’re doing is the best option possible.

The analytics is where the magic happens. Not many companies look at what happened after harvest. Premier Crop uses our platform to make informed decisions based on what the growers data is proving through on-farm trials, Learning Blocks and Enhanced Learning Blocks to provide statical confidence to help the grower see their profit.

Not every operation has the same goals and not everyone sets out to produce the max amount of bushels. It’s a “do it and check” process. We go out and do something, we check our work, and then we make corrections for the next year. As a grower, you’re always busy. You are going from one thing to the next, and there’s always something to do. Going through the data can be a tedious task that leaves you feeling like your time would’ve been better spent elsewhere. The benefit of working with a Premier Crop Advisor is that we retrieve the data, clean it up, and enter it into the system. A grower just needs to hit “record” when they’re running through the field.

Want to learn how you can work with an Agronomic Advisor to start making agronomic decisions based on your economics? Contact us to schedule a demo today.

Learn more about the farm profitability.