It’s hard to avoid hearing about the promise of “big data.” Thanks to Edward Snowden’s proposition, we need your non- partnership to use your data to revelations, it is also easy to spin conspiracy theories. There are many big-data analytics examples cited, such as Amazon and Netflix. They suggest books and movies we may enjoy based on what we have “liked” in the past or what other people who seem similar to us like. Google, the National Security Agency and others evidently collect data about what we search, what and whom we email, and much more.

There seem to be several “values” from big-data analytics. Many companies’ goals are to monetize data through better value propositions to their customers, like selling advertising, how they position products, differential pricing, etc. Another goal is to reliably predict behavior. For example, Bob shares a common background and behavior as Tim, and Tim likes this brand; therefore, Bob must like it, as well.

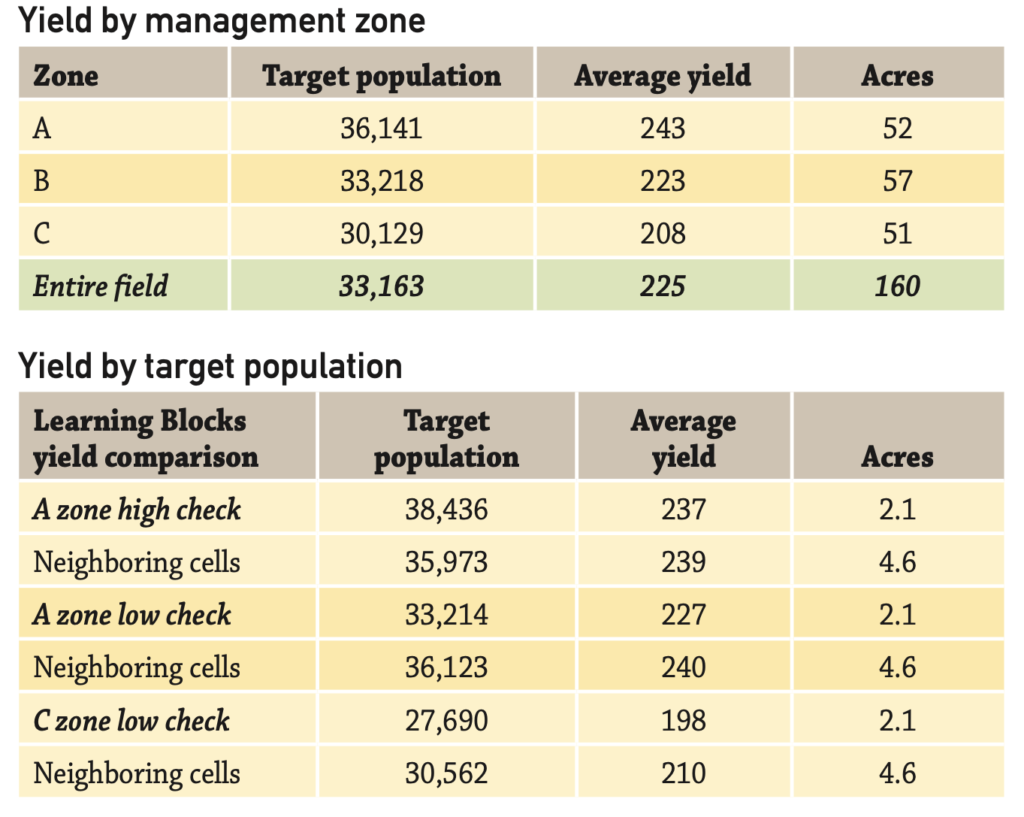

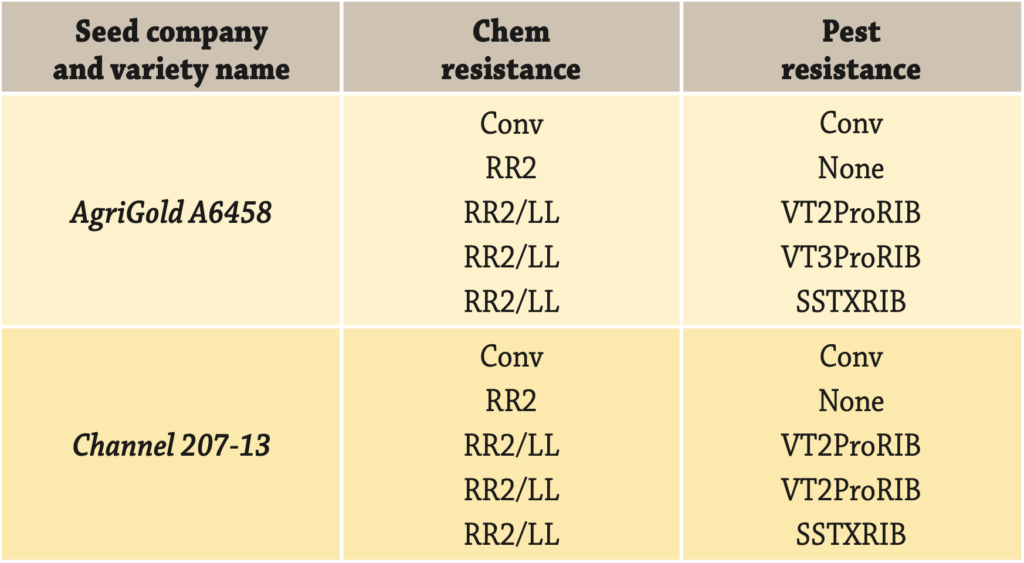

Reliably predicting behavior, better product value propositions and differential pricing are all examples of how companies could use your agronomic data. For example, your field’s soils are X, Y, Z, and hybrids A, B, C outperformed hybrids Q, R, S on 85% of the X, Y, Z soils; therefore, A, B, C is the best value proposition for you. The fact that your soils are X, Y, Z is “public knowledge” — because the soils data- base is public.

But a company might say, “to really perfect our value proposition, we need your non-public agronomic data. Why don’t you send us your historic yield data, your fertility data, your management information, etc.”

What can it hurt? After all, they only want to help you. The reality is, we all share “our” data with other companies, either intentionally in exchange for a benefit or inadvertently because we wanted a cool “app,” and sometimes the trade-offs are worth it.

For me, the difference between consumer data sharing and sharing your georeferenced agronomic data is profound. Your reading choices might influence what advertising you see; your agronomic data is your “business” data. There is nothing anonymous about GPS data.

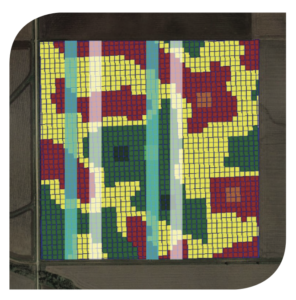

Anyone with a tractor guidance system has heard about different levels of GPS accuracy. Any of those accuracies are more than sufficient to provide site-specific data about your fields when you use a documentation system.

For Premier Crop, building a partnership to use your data to make better agronomic decisions has always begun with this foundation: The grower owns the data, data is only pooled with permission, and even pooled data belongs to and is for the benefit of the growers who shared data. But Premier Crop’s history and operating principles don’t mean that’s the right way or the only way to use data to benefit growers.

Sharing your data with seed, crop protection, nutrient or machinery suppliers can make business sense. These companies sell you products that are important to your business and profitability. Sharing your data to help them provide better recommendations may well be worth any trade-off. Most important is to think through those trade-offs and each “partnership proposal.”

Got data?

-

What are the partners going to do with the data? Perhaps more importantly — what will they assure you (in writing) they will not do?

-

Some of your partners may be fearful of missing out on the “next big thing” if they provide the wrong answers to your questions. What questions are you asking?