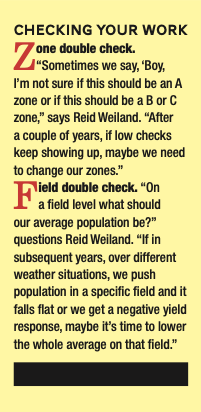

A successful crop means checking your work to track trends.

Blocks have always been linked to learning.

As children, we used blocks to build, testing our theories about the world around us. Stacked and knocked down, these wooden chunks were used to enclose spaces and bridge gaps. They helped us repeat and refine ideas.

It’s a concept that has crossed over into agriculture as farmers experiment with new ways to push every acre of dirt to its fullest potential.

“Every grower, every field, every year is unique,” says Dan Frieberg, President, Premier Crop Systems LLC. “What’s important is continuing to learn, to be willing to verify results and check your work. Our Learning Block concept helps growers continually refine prescriptions and drive yields higher.”

Real-World Application

For decades growers relied on the outcomes from others’ plots to develop recommendations that fit the variability in their own fields.

“Everything we’ve done in agronomy has been based on results from someplace else. A grower then extrapolates the data to fit his fields,” notes Frieberg.

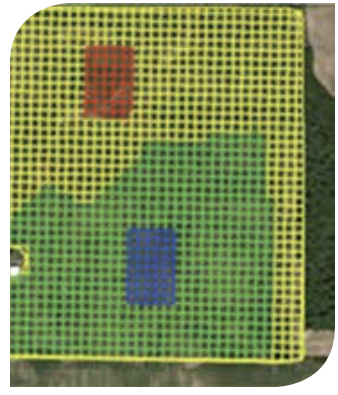

With Learning Blocks, which are portions of land ranging from one to three acres, a grower can create his own test plots to verify the technology he’s bought into is truly working.

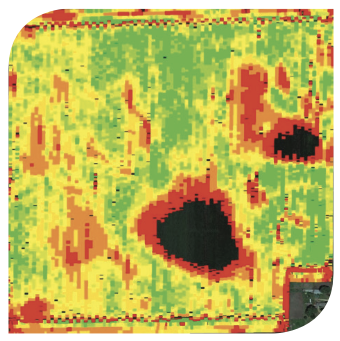

If a grower wants to verify that the variable rate seeding populations he’s implemented are maximizing his field’s potential, he can set up low and high check blocks within management zones. After harvest, an algorithm developed by Premier Crop Systems pulls yield information from the neighboring area adjacent to the blocks and compares the results to verify the population assigned in that zone is being optimized.

For example, if a target population of approximately 38,500 yielded 217 and the neighboring cell with a population of about 36,000 yielded 221, the farmer knows he spent 2,500 more seeds yet lost four bushels per acre.

“It’s a variable rate application a grower can actually see and measure without the high dollar investment and risk,” says Frieberg. “As an advisor, if I suggested to a grower to plant 38,000 in the best part of his field, he might have terrific anxiety about that. Yet, almost every grower would risk two acres because he wants to know how high is high enough. Learning Blocks are a way to take a chance but not risk a lot.”

Gaining Momentum

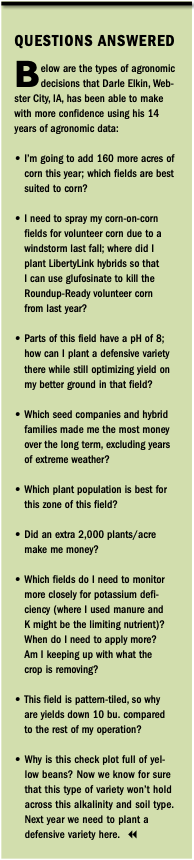

Garner, Iowa, farmer Reid Weiland knows gaining momentum involves taking risks. Yet, experimenting with the soil wasn’t something he and his father, Don, did much of.

“We were not ones to do a lot of trials on the farm because of the extra time it took,” says Reid. “It just wasn’t how we were set up.”

Learning Blocks allow them to undertake lots of trials without disrupting the flow of the operation, especially in a year like 2013 when the window to plant was so tight due to frequent rains. With a click of a button to load recommendations, Weiland is gathering data to help him better manage the family business.

“We can use Learning Blocks without slowing down because it’s all done basically in the winter,” he explains. “You set up in the winter and analyze in the winter. At the end of the year you generate so much data with really no operational effort at all except for some background GIS work.”

Like many growers, the pair already owns a variable rate planter and yield monitor, so no added investment was needed on the iron side. Yet, there is one area that requires an upgrade. “The difficulty we as producers run into is investing the time to ensure we keep good records and have good data integrity – i.e. investment in management,” notes Weiland.

Beyond management, there are other benefits to be harvested.

“Depending on your variability, you can save enough expense on your poorer quality areas to pay the consultant’s bill and then have the top side open on the better quality acres to increase productivity through investment in higher levels of inputs. Increasing productivity through higher levels of inputs is hard to put a pencil to, but conceptually I believe it makes sense,” says Weiland.

For example, let’s say you farm 80 acres and approximately 15 acres are eroded sidehills or sandy knolls.

“Because you’ve been planting a flat rate or don’t have refined zones, you could be planting 35,000 plants when it is better agronomically to seed 32,000,” explains Weiland. “At $3.50/1,000 seeds you could save yourself $10.50 on 15 acres. This isn’t big money, but then think about the extra P and K and nitrogen you’re putting on because you’re not using zones. You could easily be overapplying $20/ acre in P and K and $15/acre in nitrogen. Now you’ve saved yourself $45.50 per acre, which adds up to $682.50 on that 15 acres or $8.50/acre across the whole 80 acres.”

Breaking It Down

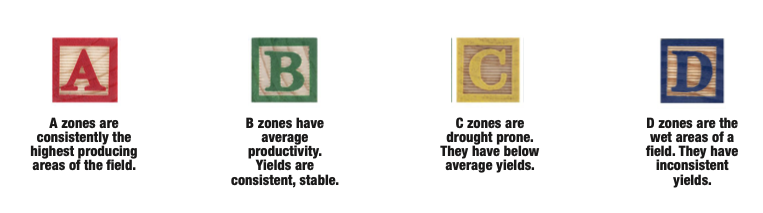

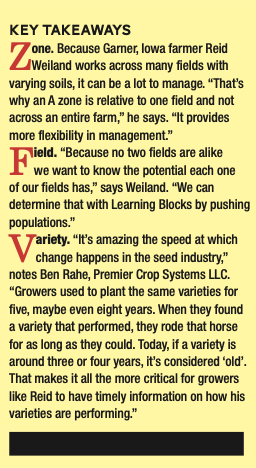

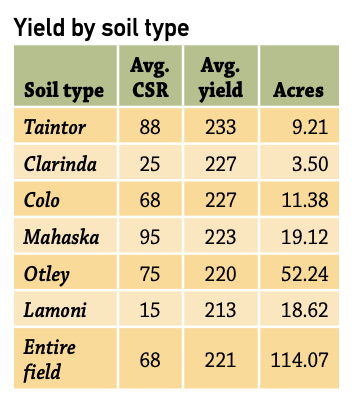

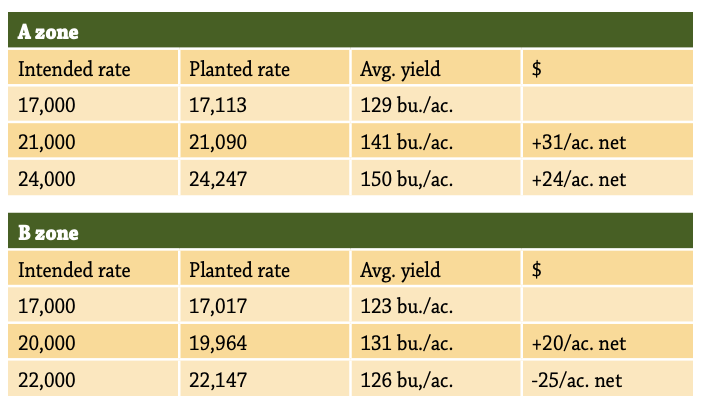

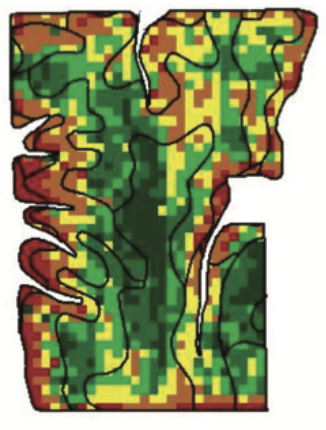

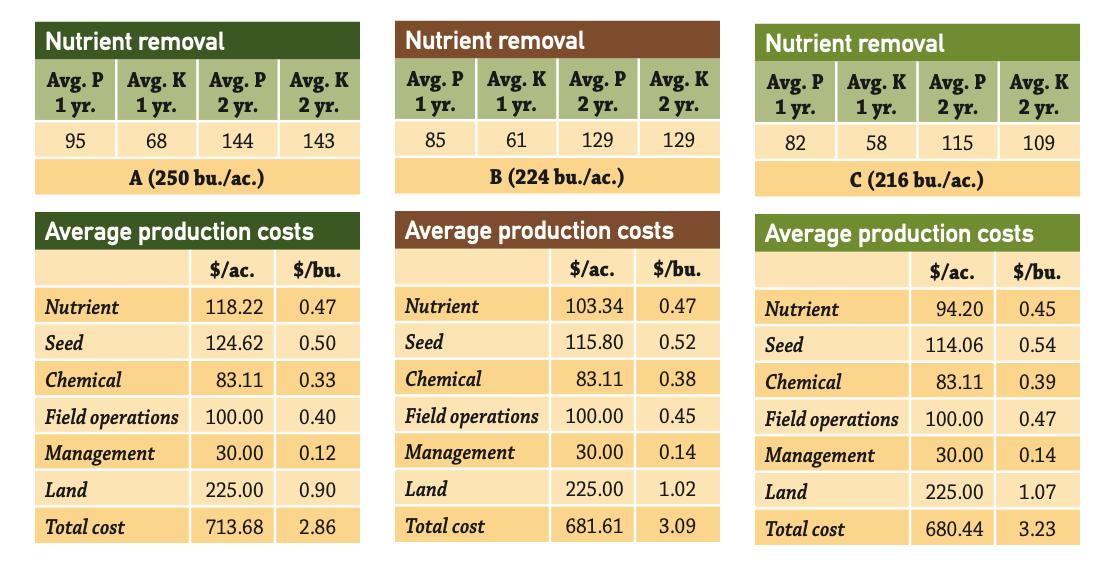

Four years in, the Weilands have divided their operation into four management zones – A, B, C and D.

“A zones are consistently the best producing areas of the field,” says Weiland. “We can identify A zones because we’ve studied multiple years of yield data, and we use that information – and common sense – to map out these ‘best of the best’ areas. They’re not necessarily tied to soil types or other physical characteristics, but they’re often well-drained, deep soils with good water holding capacity. We’re most aggressive with nutrient applications and plant populations in the A zones because our odds of getting a return on investment are best there. B zones share some of those same characteristics, but produce at the field average. Their yields don’t jump out at you like the A zones do, and so we maintain normal management practices there.”

Their C zones are the lighter, sandier soils; while the D zones are heavier soils with drainage problems.

“D stands for drown outs,” jokes Weiland.

Because no two fields are alike, one may only have an A and B zone while another may have an A, B and D zone.

“Working with Premier Crop over the last several years has taught us that an A zone on one field is not the same as an A zone in another field,” he notes. “An A zone is relative to one field and not across the whole operation. This provides more flexibility in management.”

With a bag of seed costing record amounts, variable rate seeding is not so much about lowering input costs but rather reallocating to push populations and reveal what a zone is truly capable of.

“With variable rate seeding on some of these farms we can save $10 an acre pretty quickly by cutting back on our seeding rate,” he says. “Yet, it’s not so much about reducing costs. It’s more about increasing yield.”

The four zones are broken down even further into Learning Blocks.

Blocks are paired in low and high zone checks so they can compare yields to the entire zone’s prescribed population.

For example, in a 450-acre field, an A zone, which is approximately 250 acres, has six Learning Blocks. Each block is 2.5 acres. Blocks

are planted at low and high check target populations and compared to neighboring cells, which are five acres.

“The Learning Blocks help us see what’s going on with our variable rate prescriptions and have become a part of our analytical process.” – Reid Weiland

“Our target population in the A zone on this particular farm is around 36,000. Learning Block #2, which is a high zone check, has a target population of about 38,800, while a low zone Learning Block will be nearly 4,000 less,” explains Weiland. “Once we have harvest data, Premier Crop Systems generates a report that tells us what the target population and yield is for each zone and Learning Block.”

Comparing the numbers, they then verify whether or not the population recommendation for the A zone is where it needs to be or if it needs a bit more tweaking.

“The Learning Blocks help us see what’s going on with our variable rate prescriptions and have become a part of our analytical process,” he says. “We feel that we’re unlocking value that hasn’t been unlocked before.”

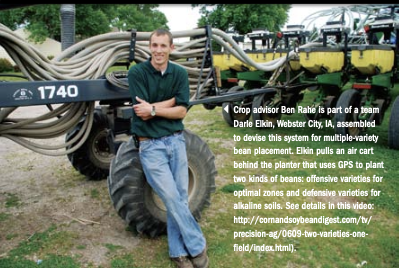

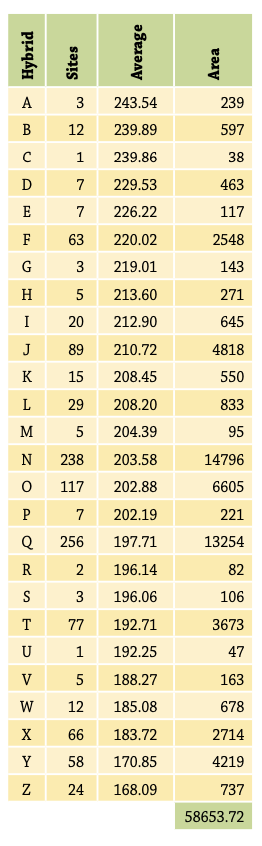

While Weiland uses the concept to ask, ‘What potential does this field have when it comes to yield?’ His Premier Crop Systems advisor, Ben Rahe, comes at it from another perspective.

“I look at it and ask, ‘What potential does this variety have? How does it respond when we push populations?’ Learning Block results can mean different things to different people,” says Rahe.

“We take it to a pretty intense level,” says Weiland. “We use them in just about every field. We look at it as an opportunity to learn every year on every variety.”

Cost Per Acre vs. Cost Per Bushel

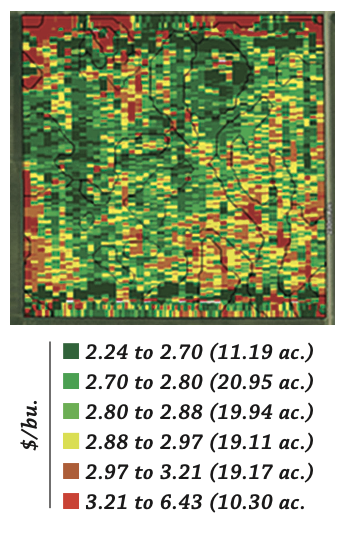

As an extension of pushing A zones, Weiland has begin to look at their fields on a cost per bushel basis instead of a cost per acre basis.

“What we as farmers have been think- ing about for so long is cost per acre,” he says. “I don’t think we’re going to throw that out the window but as acres become more important and valuable, we’re going to have to shift that paradigm to cost per bushel. Once we begin to think in that paradigm the idea of pushing our A zones becomes natural.”

Weiland adds that, “If we can raise our productivity, our cost per bushel is driven down without changing our cost per acre. In a world where we have $20,000 per acre land what’s going to be the driver is your cost per bushel not your cost per acre.”

While times are good in agriculture right now, productivity is what counts when times get tough because you can only cut costs so much.

“As an example, over the past 20 to 30 years, when things get tough P and K are where farmers cut costs. But those nutri- ents are the foundation of our crop yields and today farmers realize that the answer is the other way,” explains Weiland. “You can’t really cut that cost without hurting yourself in the long run.”

Yet, you still have to drive that planter across every acre.

“Even if you cut P and K, you still have those base costs,” he says. “If you can raise that revenue on the other side through yield and drive the cost of your planter pass down, that’s where we’re going to better our margins. That’s what Learning Blocks are all about.”

Originally published by Laurie Bedord in Agriculture.com.